Crafting a new interpretation about the recent protests in Hong Kong entails a number of decisions about content, focus and analysis. The anti-extradition law collective action is the most significant and highly documented protest in Hong Kong history, with multiple monographs already published and scholarly archives in development. It has built on the history of Hong Kong activism for universal suffrage. The issues at stake implicate fundamental differences in worldviews and unprecedented commitments to support them.

This discussion identifies the salient political events and takes the view from the street through the DIY poster culture of public documentation and its representations of police activity. It pivots to contextualize the global city by comparison to the territorial status of Hong Kong in the People’s Republic of China (PRC), in which Hong Kong is a special administrative region (SAR) subject to the potential of calculated institutional change.

The 2019–20 anti-extradition collective action marks a plateau in the Hong Kong movement for universal suffrage. The 2019 local District Council elections demonstrated its significance and success. On 24 November 2019, Hong Kong citizens voted in unprecedented numbers for pro-democracy candidates. In the four years from 2015, with the exception of one outlying district, the districts flipped from ‘Pro-Beijing’ control to ‘Pro-democracy’ control. Although the Islands District also elected a majority of democrats, the number of legacy ex-officio positions maintained the pre-existing majority.

The election landslide was not anticipated by the state. The Hong Kong government and the PRC central government regrouped in anticipation of the more significant September 2020 Legislative Council election. Before it could take place, the central government promulgated a state security law that is rendered in English as the National Security Law. Subsequent to its implementation, on 30 June 2020, the Hong Kong government disqualified several pro-democracy candidates, banned the annual July 1st citizens’ march for universal suffrage, and postponed the Legislative Council election.

The state security law seeks an expansive mandate. It would make criminal, anywhere, the representation of language that places ‘Hong Kong’ in relation to words alone that suggest its separation from the PRC. Its meta-philosophy is party-state integrity or the authority of the Chinese Communist Party and sovereign power over state territory and its representations. Hong Kong citizens apprehended such claims. In early July 2020 people gathered in small numbers, on the street and in shopping malls, and held up plain white sheets of A4 paper. Even the display of blank A4, witty if cynical, resulted in arrests. Reaching to describe the situation, the author and journalist Louisa Lim adopts the Kafkaesque and Pythonesque. The police detained one citizen for shouting ‘long live Liverpool’ after the team won its first Premier League title in thirty years.

The September 2019 District Council elections followed months of organized action against the Hong Kong government-proposed extradition bill, formally the Fugitive Offenders and Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Legislation (Amendment) Bill. The amendment would allow the extradition of Hong Kong citizens to mainland China for alleged criminal offences, i.e. from a jurisdiction based on an executive-led legislature with a relatively independent judicial system, to the legal regime of the Leninist state that returns guilty verdicts in criminal cases at rates greater than ninety-nine percent. Beginning in March 2019 the Civil Human Rights Front organized marches to protest the bill.

Hong Kong has a significant history of organized, largely peaceful social movement activity. In June 2019 clashes between the police and protesters changed the tenor of events. Outside the Legislative Council building, on 12 June, police confronted a protest group seeking to prevent the second reading of the bill. Based on footage of the scene, Amnesty International concludes police unlawfully used batons and rubber bullets in violation of international human rights law. Police authorities subsequently called the protest a ‘riot’, which invokes a colonial era tactic, and is a criminal offense punishable by a ten-year prison sentence. On 15 June the Hong Kong government announced the bill would be suspended, but not withdrawn. An estimated two million people, a new high for Hong Kong civic action, marched the following day. In response, the Hong Kong Chief Executive performed an apology to the people but did not withdraw the bill.

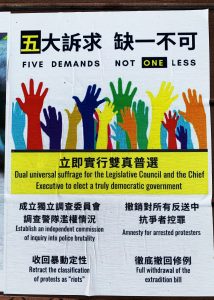

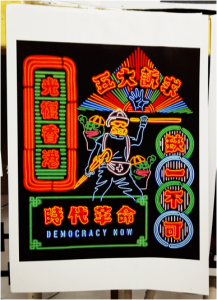

People’s concerns commensurably expanded and coalesced in the position statement ‘Five Demands, Not One Less’: full withdrawal of the bill, an official inquiry into police brutality, amnesty for arrested protesters, retraction of the ‘riot’ classification, and universal suffrage for the Legislative Council and Chief Executive. Figures 1 & 2. The poster in Figure 2 updates the aesthetic of local neon signage and combines the five demands statement with a popular slogan that is currently defined by the state as unprintable and unsayable.

- Figure 1. ‘Five Demands, Not One Less’

- Figure 2. ‘Five Demands, Not One Less’

University of Hong Kong poster wall, Mong Kok public passageway, Hong Kong, October, 2019. All photos: Carolyn Cartier.

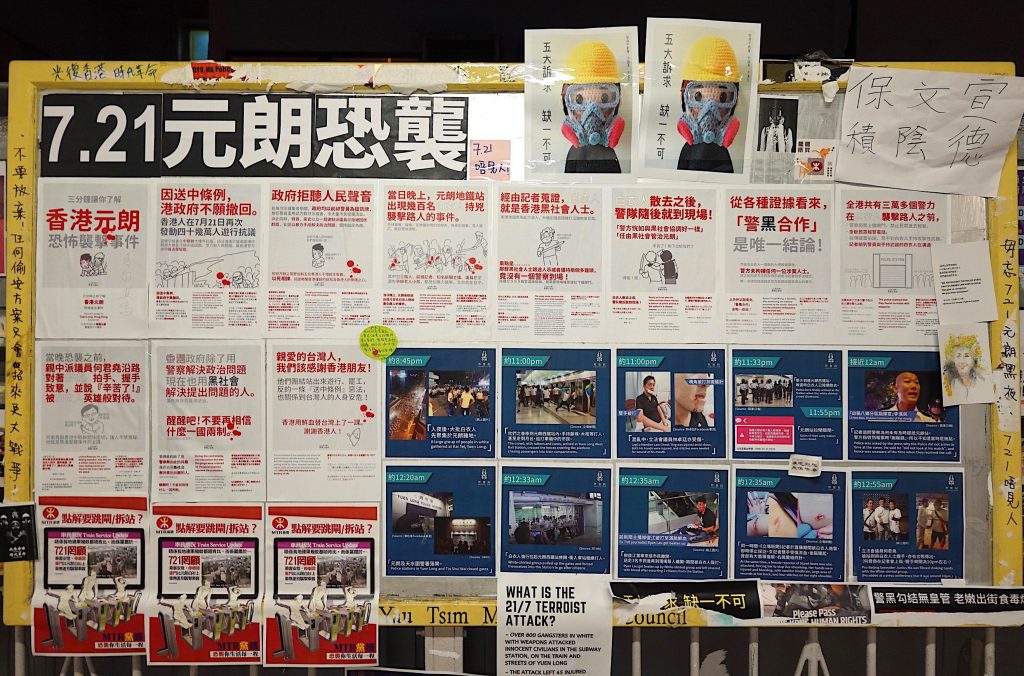

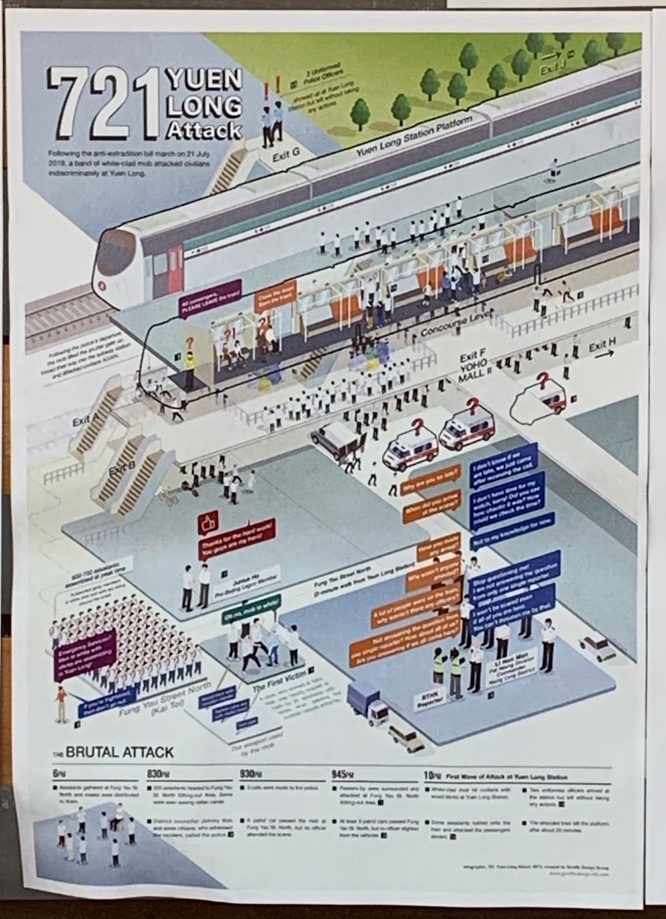

Where the authoritarian state surveils its representations, symbolic politics are never far from the surface. At the end of the route of the July 21st march some participants continued west across Hong Kong island to Sai Ying Pun, location of the Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. The national symbol of the PRC on the façade of the Liaison Office became a target, reportedly, for ink balloons. That night a group of ‘thugs-for-hire’ attacked people in the Yuen Long MTR station, some ostensibly returning from protests ‘because they were wearing black’. Filmed and posted to social media, evidence of the attack ricocheted worldwide and electrified the indignation of already outraged publics. In subsequent weeks and months documentation of the 7.21 Incident appeared widely around town. Figures 3 & 4. Meanwhile the Liaison Office erected a plexiglass barrier over the symbol of the state. As a discerning local headline captured it, ‘Safety first for national emblem’.

Figure 3. ‘7.21 Yuen Long Attack’. Yau Tsim Mong District Council Community Notice Board, Mong Kok, Hong Kong, October 2019.

Figure 4. ‘7.21 Yuen Long Attack’. Infographic. University of Hong Kong poster wall, January 2020.

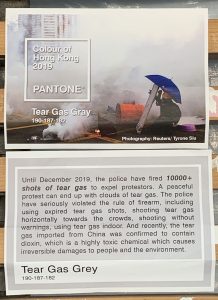

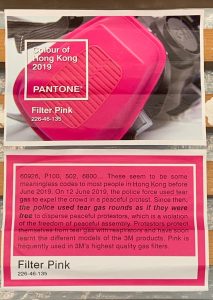

Policing diversified in forms and practices and expanded across the second half of 2019. New ordnance on display became a subject of rational documentation as if in the public interest. The police rolled out armored-vehicle-mounted long-range sonic devices and water cannons firing blue-dyed water to mark people for potential arrest. They fired tear gas inside shopping malls. The materialization of intensified policing became the execrable talk of the town. It is also becoming a subject of analysis in united front-work. Victoria Tin-bor Hui characterizes the escalation of policing in Hong Kong in 2019 as Beijing’s development of struggle and violence in order to govern it.

The international mediatization of social movement activity has magnified the episodic street protest. It contributed to naming the Umbrella Movement in 2014, which followed the pro-democracy campaign Occupy Central with Peace and Love, 2013–14. The umbrella had become a piece of street gear, a practical shield. (The 2011–12 Occupy Central protest allied with the global movement against socioeconomic inequality.) In 2019 the confrontations between umbrella-shielded, gas-masked protesters and police tactical units, facing off in gleaming high-rise canyons of the global financial district, marked by gleaming towers, yielded cinematic footage for local and global audiences. Protesters’ practices and tactics ‘like water’, Telegram-based, and color-coded, gained regard for innovative collective action. Figures 5 & 6. Color codes for the consumer landscape, for instance, communicate about shops and restaurants in relation to what political commitments their profits accumulate. The community notice board in Figure 7, like the one in Figure 3, is in Mong Kok, the established shopping district in Kowloon at a distance from downtown cores.

- Figure 5. ‘Pantone: Tear gas grey’

- Figure 6. ‘Pantone: Filter pink’

University of Hong Kong poster wall, January 2020.

Figure 7. ‘Mong Kok “stop purchasing” map’. Yau Tsim Mong District Council Community Notice Board, Mong Kok, Hong Kong, October 2019.

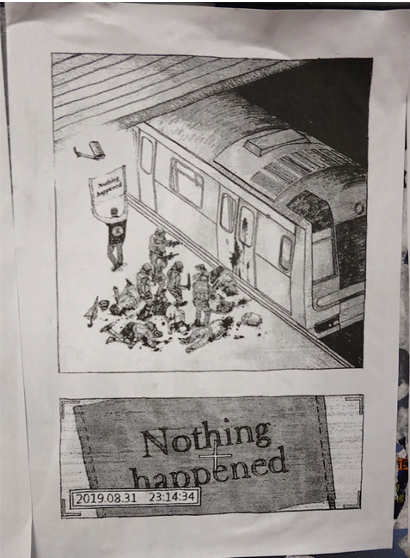

Notice boards in the districts serve as sites of information in the public interest on matters of prevailing concern. The 8.31 Incident at Prince Edward MTR station also dominated the DIY poster culture in Mong Kok. On Saturday night, 31 August 2019, according to the government-affiliated English-language newspaper of record, police tactical units ‘in pursuit of anti-government protesters enter[ed] train carriages and beat people with batons and pepper spray’. The free press version records police units ‘indiscriminately assaulting passengers with batons and pepper spray’. What is not contested is that people in the Hong Kong MTR were beaten and pepper-sprayed. The Mass Transit Railway Corporation, majority owned by the Hong Kong government, refused to release portions of the relevant close-circuit television, and since then rumors are that some passengers did not walk out of the station. Figure 8. The emergent critique of the MTR, in response to this incident and others, circulated among concerned publics and reterritorialized authority in the moral consciousness of the people.

Figure 8. ‘Nothing happened’, Mong Kok public passageway, Hong Kong, October, 2019.

Simon Schama has already placed the Hong Kong 2019 collective action alongside “Gandhi’s India, Mandela’s South Africa and Martin Luther King’s Alabama march.” Contending worldviews are at stake. The sophisticated PRC media apparatus, producing information for domestic and international audiences, circulates discursive nationalism in which social movement activity reflects the influence of so-called hostile foreign forces. According to the current Chinese Ambassador to the United States of America, for instance, ‘The biggest peril for “one country, two systems” comes from ill-intentioned forces, both inside and outside Hong Kong, who seek to turn the [special administrative region] into a bridgehead to attack the mainland’s system and spark chaos across China’. Similar concerns about ‘color revolutions’ appear widely in the state media.

The PRC is what the constitutional law scholar Guo Yanbin calls a composite state in which Hong Kong is analogous to a city-state with autonomous powers. Hong Kong in the PRC is the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region or the Hong Kong SAR. Its constitutional basis is the Basic Law of Hong Kong, established in the 1984 Sino-British Joint Agreement, an international treaty, which states the ‘capitalist system and way of life shall remain unchanged for 50 years’ under a ‘one country, two systems’ arrangement. When Hong Kong became an SAR at the end of the British colonial era it appeared to be a novel bridge across complex differences in political-economic systems.

The context challenges comparative research. To what cities in 2019 should Hong Kong be compared—Barcelona, Beirut, Berlin, Bogotá? As one headline proposes, “Hong Kong is one of the most unequal cities in the world. So why aren’t the protesters angry at the rich and powerful?” The idea of a great commercial city coming under authoritarian governance runs antithetical to concepts of the global city, world city, and municipality. After the ‘lost decade’ in Japan, the 1990s, the ungainly yet apt NY-Lon-Kong emerged in Asian city talk as Hong Kong replaced Tokyo in Saskia Sassen’s triumvirate. Like the Editorial Board of the Financial Times says, ‘Hong Kong’s status as a media hub, with robust protection for freedom of expression, is an important part of the mix that made the territory Hong Kong one of the great global cities’. It is this understanding about Hong Kong as the global city of the Asia-Pacific that retrieves the municipality from its pedestrian assignments.

The urban political concept of the municipality, a self-governing city with autonomous rights, appears in the French municipalité as a town, city, or district with local self-government. The meaning extends to the people of the city or body politic. Its deeper etymology is the Latin municipium. In The Municipalities of the Roman Empire, James Reid inquires, ‘What then were the marks by which the Greeks and Romans were enabled to distinguish between the city and the village? … The first and most vital characteristic of the normal municipality was that it should possess either complete local autonomy or a large measure of self-government’. It is noteworthy that the municipality emerged with civic self-government on whose functioning empires depended.

But the reality of Hong Kong in the PRC presents a territorial problematic. The SAR is a province-level administrative division in China, not a city. Contrary to its global city profile, the Hong Kong SAR means something other than a city in China. In the Chinese system of administrative divisions, the SAR is a revision of an historical concept for areas that require a different governing approach. In the imperial era special administrative areas were implemented along frontiers where local populations contended with the expansionary Qing empire (1644–1911). Contemporary administrative divisions are also subject to reterritorialization, historical revision, and policy change.

Among types of changes, relatively moderate forms include changes in the functional relationship and the ‘alteration of the dominant-subordinate relationship’. An apparent indirect adjustment of the functional type took place two months before the central government implemented the state security law. In April 2020 the Chinese central government declared, in a clarification, the Liaison Office in Hong Kong was not bound by Article 22 of the Basic Law, which articulates the prevention of interference by PRC units and departments. Confusion ensued over the ‘clarification’, which rescaled the office from subsidiary to outranking, or outflanking, the Hong Kong government. The announcement compelled Anson Chan Fang On-sang, Chief Secretary at the transfer of Hong Kong from British colony to PRC sovereignty, to write, “The office was never supposed to play a role in Hong Kong’s policymaking and day-to-day administration, let alone become a centre of power.” Struggles on the ground refract understandings about such mutable power relations.

Latent transmutations also inhere in political text. Where legal analysts seek to read in ‘one county, two systems’ predictable norms, the PRC leadership periodically intones that one country is more important than two systems. The contingent analysis is that yiguo liangzhi (one country, two systems) is a type of tifa or formulation in the dialectics of political thought, as Michael Schoenhals explains in Doing Things with Chinese Words, which the state may reinterpret to suit new goals. The Chinese central government has recently articulated some of these in the state security law attached to Hong Kong. The text of that law, in reflection on the anguished history of foreign imperialism and extraterritoriality on the China coast, would paradoxically sketch a new extraterritoriality with global reach. It would also override the September 2019 withdrawal of the extradition bill.

In Undoing the Demos, Wendy Brown writes ‘When the domain of the political itself is rendered in economic terms, the foundation vanishes for citizenship concerned with public things and the common good’. We are meant to understand Brown’s evaluation as a general condition of the malaise of democracy wherever neoliberalism flourishes, and the global city of Hong Kong swells with inequality driven by capitalist freedoms. Via this logic the government has compelled business elites to support the new security law. Yet distributions of power and possibilities of expression underpin the political systems at the center of Brown’s critique, making it, on a comparative basis, perhaps a relative indulgence. On the original date of the Legislative Council election, 6 September 2020, citizens gathered in public space to share concern about its postponement, and some 300 were arrested. Meanwhile a memory hole opened to ‘restore the truth’ about the 7.21 Incident.

The politics of language meets the language of politics in democratic centralism, the organizational principle of the CCP in which debate and decision-making on behalf of the people take place only within party ranks. The unitary state formation precludes political freedoms including universal suffrage. Hong Kong is the only place in China where a social movement for liberal freedoms takes place. Though the District Council election is a relatively minor affair, through the ballot box Hong Kong people effectively rejected the sovereign. District councillors in Hong Kong work only for community interests, yet they represent the city and the grassroots. In response the party-state seeks to universally control the political discourse, which demonstrates a certain understanding of the global city.

Carolyn Cartier is a professor of geography and China studies at the University of Technology Sydney. Currently working on the administrative divisions in China, she is a founding member of the UTS China Research Centre (2009–14) and a founding fellow of the Australian Centre on China in the World at the Australian National University.

All essays on Urban Revolts

Introduction: The Spatiality of Street Protests before and during Covid-19

Liza Weinstein

When the Pandemic Meets the Insurrection. Santiago, Chile

César Guzmán-Concha

Urban Revolutions: Lebanon’s October 2019 Uprising

Mona Fawaz & Isabela Serhan

The Revolt of the “Periphery” Against the “Metropolis”? Making Sense of the French Gilets Jaunes Movement (2018-2020)

Claire Colomb

An Urban Perspective on the Colombian “Paro Nacional”

Sergio Montero & Isabel Peñaranda

The Predicament of Hong Kong and the Spatial Expanse of Territorial Governance

Carolyn Cartier

Published online October 2020

Related IJURR articles on Urban Revolts

Institutionalization and Depoliticization of the Right to the City: Changing Scenarios for Radical Social Movements

Sergio Belda-Miquel, Jordi Peris Blanes and Alexandre Fredian

Do‐it‐yourself urbanism and the right to the city

Kurt Iveson

Glocalizing protest: urban conflicts and the global social movements

Bettina Köhler, Markus Wissen

Permitting Protest: Parsing the Fine Geography of Dissent in America

Don Mitchell, Lynn A. Staeheli

The Urban Question Revisited: The Importance of Cities for Social Movements

Walter J. Nicholls

Urban Segregation and Metropolitics in Latin America: The Case of Bogotá, Colombia

Joel Thibert, Giselle Andrea Osorio

© 2020 THE AUTHOR. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF URBAN AND REGIONAL RESEARCH, PUBLISHED BY JOHN WILEY & SONS LTD UNDER LICENSE BY URBAN RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS LIMITED

This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License, which permits use and distribution in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, the use is non-commercial and no modifications or adaptations are made.