“The war against terrorism must be conducted across Europe in ‘cold blood’”, France’s President François Hollande declared shortly after a series of attacks in Brussels on March 22, 2016. The Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi quickly joined the fray, adding that “Our enemies are already inside our cities”. Their comments reflect an important element of the global “war on terror”, which has continued unabated for over a decade. What began as a purported response to a threat posed by a small group of militants in the Middle East has been transformed and extended into a permanent and boundless war, which is increasingly turned inwards, to be waged domestically inside urban spaces across the world (Graham 2012). Bernard Henri Levy, a French intellectual and proponent of military interventions in Libya, Syria and Gaza, has warned of a “metrocide” threatening Western cities, arguing that “all fascist movements hate cities, because they symbolize and embody civilization […] and Islamofascists are no different”. The city has thus become the new arena of modern warfare; its strongholds are the nodes of power and authority, of governance, capital and culture that give rise to the city as we know it.

One of the grim products of this transformation is the militarization of our cities, a process in which the urban landscape is re-designed, through architectural, political and social interventions, to facilitate a greater degree of surveillance and control by military or military-like security actors. Urban militarization evokes the fantastic image of soulless, “prisonlike inner cities, high-tech police death squads […] and guerilla warfare in the streets” (Davis 1992: 223-224). Yet such a dystopian vision obscures the variety of ways in which military urbanism takes shape, some more subtle than others: from the hostile architecture dominating public space to the securitization of educational and social services, from the targeting of minorities as ‘security threats’ to the proliferation of private security agents in the streets. Militarized cities do not all look alike. Different cities are characterized by different policies and responses to the threat of war, shaped by their specific political, social and historical contexts. A comparative approach to military urbanism can highlight these specificities amongst more generalizable responses. This piece, focused on the militarization of Brussels (Belgium) and Jerusalem (Israel-Palestine), compares the different courses taken by public security officials facing increased security threats and international scrutiny in complex urban settings. I conclude by proposing an examination of militarism not only in terms of technology (Philips 2016), policy-making (Molotch and McClain 2003) or the criminalization of urban resistance (Graham 2012), but also as a constitutive process of reformulating the relations between the state and its urban citizens, and of sorting between those residents considered worthy of additional protection and those targeted as potential threats. As I show in this essay, this differentiation of citizenship is achieved in different ways in different cities, through divergent politics and performances of military visibility.

Brussels, the capital of Belgium and the seat of the European Commission, European Council and NATO, is a city known for its laissez-faire attitude in which different communities live side by side. From the neat and orderly European quarter to the mixed neighborhoods with soundscapes dominated by Arabic, Brussels is known as a hectic, yet peaceful city. Despite inequalities in public spending between the different municipalities that comprise the capital, the city saw little of the upheaval witnessed in the suburbs of Paris or Stockholm. Brussels’ decentralized urban mode of governance permits local authorities a degree of control over police matters, mitigating the strong-arm policies often advocated on the national level. The last few years, however, did see growing public anxiety over the old and new threat of terror; the ongoing war in Syria and Iraq attracted hundreds of Belgian Muslim youth to Middle Eastern battlegrounds, many of whom subsequently returned to Brussels.

Soldiers stationed in central Brussels (17.7.2016). Photo: Ronan Shenhav, CC BY-NC 2.0

Belgian public security officials faced growing pressure to ramp up counter-terrorism efforts, especially after an attack on the city’s Jewish Museum in 2014. Yet due to Belgium’s fractured political landscape, Brussels’ decentralized police administration and years of budget cuts, public security personnel were spread thinner than ever. The government’s response was the deployment of soldiers to the streets of Brussels and other major cities for the first time in decades. What began as a minor deployment of 300 soldiers to safeguard specific ‘sensitive’ locations, such as the Jewish quarter in Antwerp and the American Embassy in Brussels, turned into a major operation following the Paris attacks in November 2015 and the subsequent attacks in Brussels in March 2016. Soldiers were stationed in every major thoroughfare, patrolling the city’s commercial districts, guarding nearly every transport hub.

The soldiers, heavily armed and dressed in full military attire, were welcomed by some residents with enthusiasm at first. Their reception was naturally not detached from local and national politics: considered as ‘outsiders’ to Brussels, many hoped the soldiers would bring order to the chaotic city. Other residents were hesitant – could the regiments of young soldiers really protect the city, or would they only contribute to further discrimination and alienation of the city’s minorities? While Brussels is an incredibly heterogeneous city, Belgian soldiers are a far more homogenous group, with Flemish soldiers constituting the majority in every rank of the country’s armed forces. As the months passed, the presence of soldiers became a part of everyday life in Brussels – but with little authority other than to stand guard or conduct patrols, their presence did not fundamentally change the city’s predicament. The deployment of soldiers to the city can thus be understood as a military form of ‘reassurance policing’ (Innes 2004), aimed primarily at showing presence by presenting a highly visible and public element of the state’s efforts against the threat of terrorism.

Unlike in Brussels, the militarization of Jerusalem can be traced to a period far before the recent escalation in violence. From the day that Israeli tanks rolled into East Jerusalem in 1967, the military never really left the city. While the Israeli army was ordinarily prohibited from operating inside Jerusalem’s city boundaries, the annexation of Jerusalem brought about the slow diffusion of military roles, capacities and technology into the city via a long list of other state and non-state security actors. The police took over public security and criminal investigations with the aid of the Israeli intelligence services; armored vehicles in the street corners were manned by border policemen; and private security companies, on behest of the state, increasingly took the role of protecting settlements, checkpoints and transport infrastructures. When the police and the judicial system are unable to convict or silence Palestinian dissidents, the Israeli Ministry of Defense can issue administrative detention orders, imprisoning Palestinian residents – legally considered a stateless population – for indefinite periods without trial. The Israeli authorities followed a well-established pattern of transplanting military strategies and technologies from the ‘periphery’ into militarized metropolitan areas (Coaffee 2003), in this case from the occupied West Bank into the heart of the declared Israeli capital, Jerusalem.

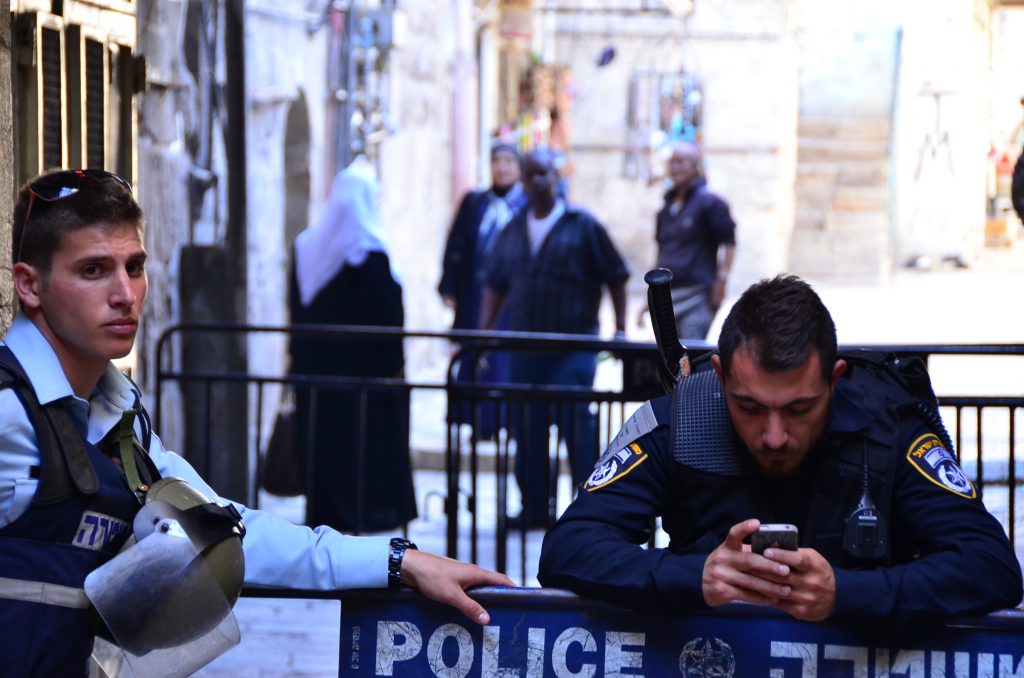

Israeli policemen manning a checkpoint in Jerusalem’s Old City (17.5.2015). Photo: Lior Volinz

The militarized security provision has been in place long enough to allow security agents – such as policemen, gendarmerie and private security guards – to adapt to the changing reality of the city. Security agents in East Jerusalem assume different roles and performances towards different audiences – striving to reassure Jewish-Israeli settlers, intimidate Palestinian local inhabitants, and remain largely invisible for the tourists that visit the city (Grassiani and Volinz 2016: 20-28). The resurgence of militarized policies – armed incursions, collective punishments and deliberate security friction – contribute to the reformulation of relations between the state and the city’s Palestinian residents, who are increasingly losing their limited rights, property and autonomy as they’re are expected to conform to its state’s military might. The circulation of people and goods – within the parameters set by Israeli officials – is maintained despite the ubiquitous presence of security personnel and the growing resistance from the Palestinian residents. The Israeli national and local authorities strive to preserve a façade of normalcy under occupation, enabling the dispossession of Palestinian residents by facilitating the unhindered access of settlers, tourists and capital flows into occupied East Jerusalem while maintaining the illusion of a unified Jerusalem under one Israeli law.

While in Brussels the strong visible presence of soldiers in public space obfuscates the inadequacies and failures of other public security agents, in Jerusalem the visible absence of soldiers in the street conceals other heavy-handed and increasingly militarized strategies and practices used in occupied East Jerusalem. The former city presents a case of a heavy military presence in lieu of militarized police personnel, while the latter offers an example of diffuse military urbanism in the absence of an army. I suggest that our understanding of the militarization of urban areas requires attending to the shifts in state-citizen relations that take place as state security provision is transformed. In Brussels, the deployment of soldiers is intended primarily to reassure the city’s wealthier municipalities’ residents and the Brussels-based international institutions, while minimalizing disruption to most residents’ lives or to the delicate relations formed over the years between the local police and the city’s ethnic and religious minority groups. In Jerusalem, the militarization of the city is aimed at reproducing differentiated citizenship between Israeli-Jewish citizens, who are entitled to ‘feel secure’ and Palestinian residents, who are addressed only as undesirable security threats. A comparative approach to the multiple facets of militarization can extend our understanding of the city, both as a securitized battleground and as a crucible in the formulation of new relations between state authorities and their citizens.

Lior Volinz is a PhD candidate at the University of Amsterdam. His research, as part of a larger research group working on the emergence of public-private security assemblages, focuses on the privatization and pluralization of security and military functions in Jerusalem and its relations to the (re)production of differentiated citizenship in a divided city.

All essays on The City at War: Reflections on Beirut, Brussels, and Beyond

The City at War

Rivke Jaffe

When the Pursuit of National Security Produces Urban Insecurity

Saskia Sassen

Diversifying Urban Studies’ Perspectives on the City at War

Mona Harb

A Balanced Response? The Quest for Proportionate Urban Security

Jon Coaffee

War, Crisis Cities, and Urban Research

Miriam Greenberg

Related IJURR articles on the City at War

Urban Security from Warfare to Welfare

Jennifer S. Light

Introduction: Symposium on Urban Terror

Harvey Molotch

Cities and the ‘War on Terror’

Stephen Graham

Security or Safety in Cities? The Threat of Terrorism after 9/11

Peter Marcuse

When Life Itself is War: On the Urbanization of Military and Security Doctrine

Stephen Graham

Guerrilla‐style Defensive Architecture in Detroit: A Self‐provisioned Security Strategy in a Neoliberal Space of Disinvestment

Kimberley Kinder

© 2017 THE AUTHOR. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF URBAN AND REGIONAL RESEARCH, PUBLISHED BY JOHN WILEY & SONS LTD UNDER LICENSE BY URBAN RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS LIMITED

This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License, which permits use and distribution in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, the use is non-commercial and no modifications or adaptations are made.