“To My Dear Community— It is with a heavy heart, great thought and consideration that I have made the very difficult decision to sell The Lexington Club,” wrote the owner of the last lesbian bar in San Francisco. Processes of gentrification ranked at the top among the reasons for closing included in the 2014 Facebook post. Lesbians were still being dispossessed of their haunts (and homes) in the city’s Mission District neighborhood. The Lex’s rent and its patrons’ drinks had become too costly. Over the next several years, lesbian bars continued to close across the US, UK, and Canada, and the mainstream, straight media erupted in shock and awe at the closing of the last lesbian bar in America’s gayest city, offering explanations ranging from gay and lesbian “assimilation” to the “extinction” of lesbian culture. The lesbian-queer media instead invoked the continual “disappearance” of the lesbian bar.

The Lexington Club, lesbian bar in the Mission District in San Francisco, at 3464 19th Street. 2014. Photo: Dreamyshade.

Ironically, these accounts repeat many of the well-trodden arguments in mainstream media and some academic writing about LGBTQ+[1] and lesbian neighborhoods. LGBTQ+ and lesbian neighborhoods were said to be declining due to the “assimilation” of LGBTQ+ culture and politics in the United States, and the “straightening” of supposedly “passé” LGBTQ+ neighborhoods (Ghaziani 2014). Yet these claims of lesbian-queer assimilationist extinction are unfounded. Instead, to understand the project of queering urban space, we must read queerness both in, across, and beyond cities.

A decade before the Lex closed in San Francisco, queer geographers and scholars writing broadly on queer space took a much-needed turn toward queer anti-urbanism (Halberstam 2005). Cultural theorist Karen Tongson (2011: 29) wrote with frustration of “the developmental logics of queer relocation starting in amorphous elsewheres and triumphantly ending somewhere—in the designated ‘place for us’ that is New York, New York.” I love New York (and I even wrote a book about it) — but I’ve long known that the queer rural is often ignored, mocked, and belittled as backward. At the same time, certain queer cities remain objects of reverence, along with the middle-class cosmopolitanism that they represent (Herring 2010).

Throughout studies of LGBTQ+ spaces and history, as well as in my own research with generations of lesbians and queers in New York City (1983—2008), bars are almost always mentioned as the lesbian-queer place — and LGBTQ+ bars are urban phenomena (Faderman 1992; Kennedy and Davis 1994; Ingram 2006; Gieseking 2016, 2020). However, the possibility to have a bar of one’s own is heavily shaped by gender, race, and class. Given the emphasis on the roles of bars and parties in LGBTQ+ lives, it is revealing that, while there were over 52 of these places for men on a 2008 Pride map of the southern half of Manhattan, there were only four bars for women[2]. Lesbian bars reached their peak in NYC in the early 2000s, when there were just eight lesbian bars in New York City. Now there are three — and none of these primarily serve people of color. Still, New York City is one of the cities to host the most lesbian bars in the world; there are two lesbian bars left in the entire UK. If we are to ever get beyond queer urbanism as a default model of queer space, then we must also look at lesbian-queer spaces that include and go beyond the lesbian bar.

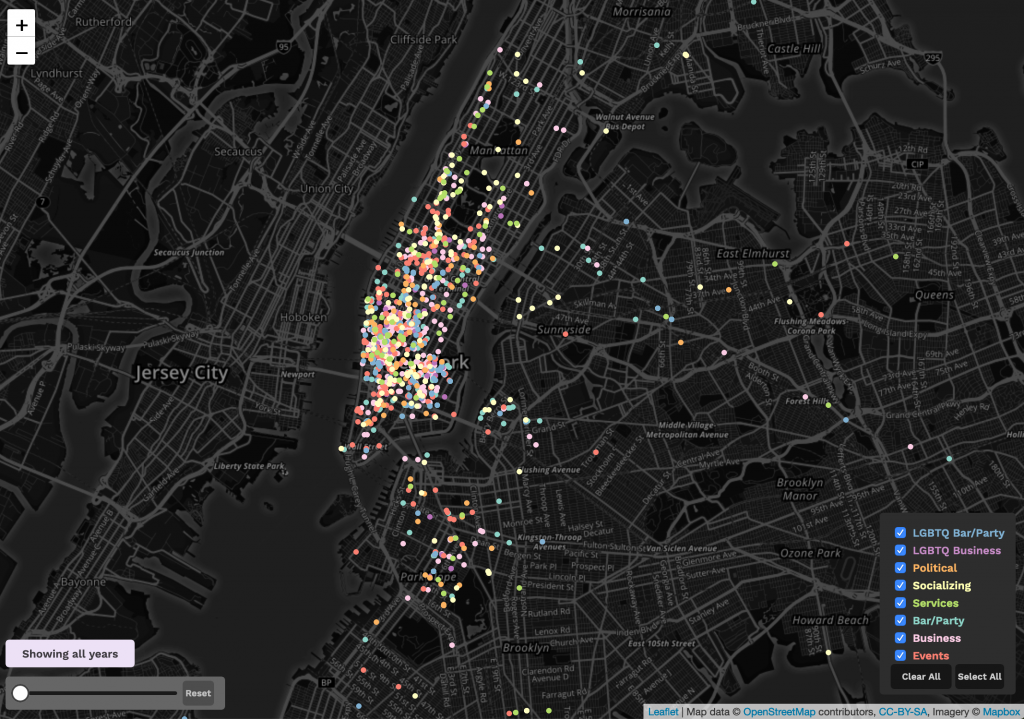

Screenshot of An Everyday Queer New York website, Jen Jack Gieseking with Lindsey Funke. 2019.

What if we were to look again to how queers resist cis-heteropatriarchy in order to create urban space? I am not suggesting we get over the dyke bar — in the words of queer geographer Natalie Oswin (2008: 100), “for as long as non-heterosexuals are discriminated against, queer spaces will remain something that … queers cannot not want.” Rather, I am arguing that the potential and prowess of this marginalized group — a group who made spaces when there was no way to do so — requires another approach. In my own research, I found that the kinds of places that lesbians and queers defined or experienced as lesbian and/or queer included a much wider range of spaces than recorded in popular LGBTQ+ history (Gieseking 2016). The companion website to my forthcoming book, An Everyday Queer New York, records over 1,600 places listed in New York City lesbian periodicals (1983—2008) (Figure 2). From the Park Slope Food Co-op to W.O.W. Café, from pick-up basketball games at the YMCA and AA meetings at the LGBT Center, to be lesbian and/or queer has required the ideal and existence of the bar, always alongside a multitude of other places.

This ability to create and claim queer physical spaces is also mirrored in the digital realm. In November 2019, just over five years after the Lex bar closed, the Lex.app launched as “a lo-fi, text-based dating and social app for lesbian, bisexual, asexual, and queer people.” The parallel in titling is happenstance: Lex founders describe the app as “short for lexicon” because it “is the only dating and social app where the text comes first and the selfies, second.” In other words, only text-based personals are featured with the option to link your Instagram profile, and users can like each other’s profiles and message one another directly. Since its launch, the upscale New York Magazine posited that the Lex.app may also “revolutionize dating” for queer people.

This is Lex, Lex.app on Instagram. Nov 5, 2019.

With the long-time fixation on bars as defining the lesbian queer space, what if the fall of lesbian bars in North America and Europe is not an end, but a beginning? The Lex app is evidence that lesbians and queers have not assimilated but rather adapted. In addition, like the course of points on my map of everyday lesbian-queer spaces, it points to a way of telling queer history that reveals how lesbians and queers, and LGBTQ+ people more generally, produce space in the face of heteropatriarchy, whiteness, colonialism, and ableism.

In the ways lesbians and queers survive and thrive on the Lex.app, the binding of queerness to urbanity is undone all the more. While a post from Lex users in New York and San Francisco appears at least once when I scroll through the app, I can also instantly connect to those who the app describes as “womxn and trans, genderqueer, intersex, two spirit, and non-binary people” beyond these urban hubs. I see people looking for advice and love, sex and connection — and below each of their names is a physical place. These places read as a roll call of places with little to no formal or even written queer history, packed with queers and their desire to know and be known to one another: Topeka, Zagreb, Calgary, Bengaluru (Bangalore), Delray Beach, Jakarta, Tampa, Oxford, Warszawa, Vancouver, Göteberg, Baltimore, Paris, and Grand Rapids, as well as Siloam Spring, Arkansas, Lutwyche, Australia, and Denmark, Maine. The production of digital places requires a geography of physical places, and those may or may not be the “queer” cities so often memorialized by the media, activists, or even scholars (cf. Cifor 2019).

The attendees and users of Lex — Lexes both past and present — never assimilated or disappeared. Lesbians and queers cannot economically and politically afford to hold on to, let alone build, physical spaces in ever-increasingly expensive cities, and lesbian-queer specific spaces are often absent beyond these cities. Instead, queers on the Lex.app are intervening in the “get thee to the big city” narrative (see Weston 1995) that fairly enrages Tongson and so many others (including myself), and they make room to tell very different tales of queering urban space, in and beyond the city and its bars. That is the story of queering urban space: queers found another way to find one another and be themselves, yet again, exactly where you weren’t expecting them to.

Jen Jack Gieseking is an urban cultural geographer, feminist and queer theorist, and environmental psychologist. He is Assistant Professor of Geography at the University of Kentucky. Their book, A Queer New York: Geographies of Lesbians, Dykes, and Queers, is forthcoming from NYU Press in 2020. Jack can be found at jgieseking.org or on Twitter at @jgieseking.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Elizabeth W. Williams, Nick Lally, and Nari Senanyake for their comments. All mistakes are my own.

All essays on Queering Urban Studies

Introduction

Rivke Jaffe

The Fraught Nature of Exceptional Gay Spaces

Ghassan Moussawi

A Tale of Two Lexes: a Lesbian-Queer Anti-Assimilationist Approach to Queering Space

Jen Jack Gieseking

Queer Regenerations of Violence, from Berlin to Toronto

Jin Haritaworn

For the City ‘Not Yet Here’

Natalie Oswin

Sex Work is Urban

Kian Goh

Into and Beyond Death: Considering Transgender Justice in Urban Studies

Rae Rosenberg

Related IJURR articles on Queering Urban Studies

Women, urban social movements and the lesbian ghetto

Elizabeth M. Ettorre

Social theory, social movements and public policy: recent accomplishments of the gay and lesbian movements in Minneapolis, Minnesota

Lawrence Knopp

Gender and space: lesbians and gay men in the city

Sy Adler and Johanna Brenner

“Out” in the Valley

Ann Forsyth

Finding oneself, losing oneself: The lesbian and gay “scene” as a paradoxical space

Gill Valentine and Tracey Skelton

Journeys and returns: Home, life narratives and remapping sexuality in a regional city

Gordon Waitt and Andrew Gorman‐Murray

LGBTQs in the city, queering urban space

Yvonne P. Doderer

Relational Comparison and LGBTQ Activism in European Cities

Jon Binnie

LGBT neighbourhoods and “new mobilities”: Towards understanding transformations in sexual and gendered urban landscapes

Catherine J. Nash and Andrew Gorman‐Murray

“Wilding” in the West Village: Queer space, racism and Jane Jacobs hagiography

Johan Andersson

The trouble with flag wars: Rethinking sexuality in critical urban theory

David K. Seitz

A clash of subcultures? Questioning Queer–Muslim antagonisms in the neoliberal city

Kira Kosnick

Urban political ecologies and children’s geographies: Queering urban ecologies of childhood

Laura J. Shillington and Ann Marie F. Murnaghan

Urban politics as the unfolding of social relations in place: The case of sexually transmitted disease investigation in mid‐twentieth‐century gay Seattle

Larry Knopp, Michael Brown, and Will McKeithen

© 2019 THE AUTHOR. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF URBAN AND REGIONAL RESEARCH, PUBLISHED BY JOHN WILEY & SONS LTD UNDER LICENSE BY URBAN RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS LIMITED

This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License, which permits use and distribution in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, the use is non-commercial and no modifications or adaptations are made.