There are no monolingual cities. The diversity of urban life always includes the encounter and exchange of languages. Conversations on sidewalks and in corner stores, the visual display of scripts on storefronts and billboards – these are key to the sensory experience of every city. The interplay among languages shapes knowledge of the city.

Urban languages do not simply co-exist – they connect, they enter into networks. This means that cities are not only multilingual – they are translational. It is translation that tells which languages count, how they occupy the territory and how they participate in the discussions of the public sphere.

Despite awareness of multilingualism, language interactions are often overlooked as a key to the creation of meaningful spaces of contact and civic participation. Translation is the key to citizenship, to the incorporation of languages into the public sphere. Understanding urban space as a translation zone offers a corrective to the deafness of much current urban theory.

What might a map of the translational city look like? Think of a familiar type of language map – the kind that shows the multitude of languages one might find in a city like New York. It would display a mosaic of colours, indicating the homes or shops where a language is spoken. But what if the map focused instead on crossings and shifts, or on zones where languages meet – places that we could call sites of translation?

Spadina Avenue in Toronto today given its indigenous name. Photo: Hayden King, Ogimaa Mikana Project – ogimaamikana.tumblr.com.

Every city will have its own map of such zones and sites, resulting from the interactions among its various home and migrant languages, and from the spatial organization of the city – the neighbourhoods, divisions and contact zones, where languages come together or are kept apart. Translation is a wide category of language exchange that includes interlingual conversation (translingualism), artistic projects (theatre, cinema, literature, music) that resuscitate forms of memory or revalidate less prestigious tongues, political activism at the junction of global movements, projects of renaming that symbolically territorialize public space, and very broadly the production of translated knowledge and the shifts in individual identity that involve forms of self-translation.

To use translation as a tracking tool is to be attentive to the direction of cultural flows (from one language to another), to changing volumes of intensity (when a language becomes culturally and politically relevant), to spatiality (the meeting places, the scenes, the symbolic sites where languages come together) and to the affects that sustain interactions (whether translation is cool or warm, pure protocol or an expression of urgency). Translation tracks connections between variously entitled communities – those that have historic claims to the territory of the city, as well as those with members who seek to establish claims as migrants, refugees or exiles.

Translators cross their cities to discover other voices and carry back their newfound knowledge. In a city like Montreal, over the period from 1940 to 1990 one could follow English-language translators as they left their home neighbourhoods and set out to establish connections with the francophone “other” side of town. Their projects were integral to the unfolding of Quebec’s Quiet Revolution during the 1960s, to the economic and political shifts which saw the emergence of a secular nationalism and to the transformation of Montreal into a cosmopolitan and predominantly francophone city. Not all these tales were success stories: some confirmed the remoteness of political communities to one another, the impassable distances that reinforced the separations. While many translation projects were animated by the energy which would create new cultural fusions, others only pointed to respective insularities. Parallel expeditions into third tongues like Yiddish, Italian or Haitian Creole increased the complexity of language traffic. Today the trajectories of translation in the city would look very different, with shifts in the landscape of migrant languages and a new temper to the dialogue between English and French.

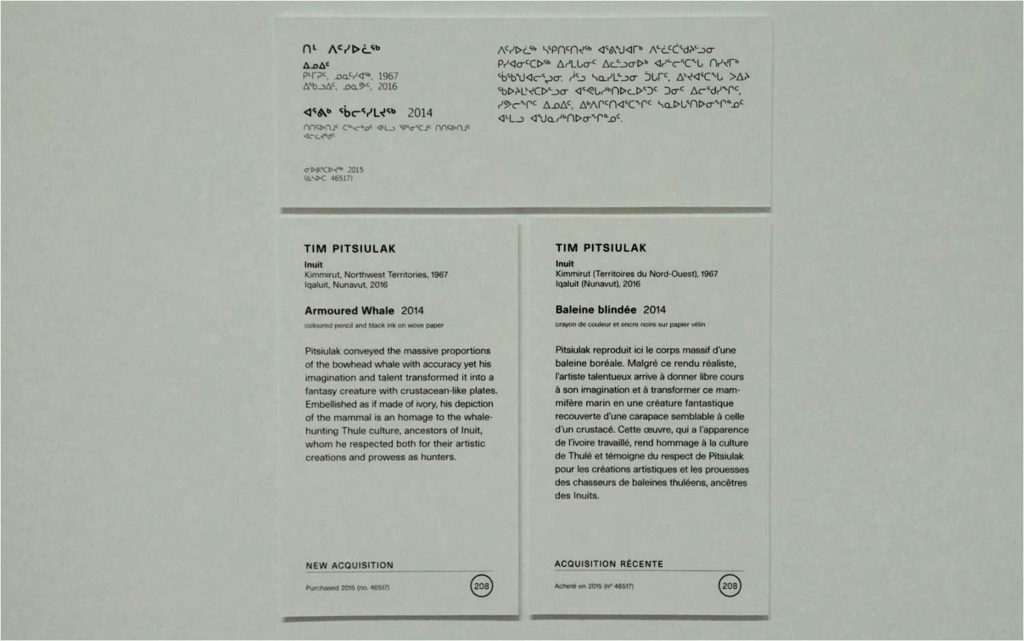

The National Gallery of Canada’s new displays of indigenous art which include labelling in the language of the community which created the work. Photo: Canadian and Indigenous Galleries, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa.

One could define categories of translational cities. Some cities experience spectacular shifts that are the result of language makeovers. For the cities of Central Europe, translation in the twentieth century was a form of violence. Their very names reflect successive territorializations: Lemberg-Lwów-Lviv, Pressburg-Pozsony-Presporak-Bratislava, Danzig-Gdansk, Wilno-Vilna-Vilnius, Czernowitz-Cernauti-Chernivtsi. Each variant of the city name stands for a new regime of political and linguistic power. Entangled in the transformations brought about by the fall of the Habsburg Empire, two World Wars, and the end of Communism, the cosmopolitan cities of Central Europe fell prey to many forms of translation.

But translation is a pendulum. The back swing recalls the violence of voices suppressed. The forward swing embraces the struggle to reanimate and reinstate those languages and the worlds they contain. Each of these cities has their “ghost signs,” glimpses of languages that resurface under the crumbling brick of a shop’s façade, announcing products to customers long gone. Messages from another time, they recall populations who have been expelled, annihilated. They also gesture towards acts of rememorialization, where the words of the past can be read again, summoning back the lost sounds of sidewalks.

If it is through translation that languages can be suppressed, it is equally through counter-translation that languages can be reanimated, brought back to the surface and into circulation. Disappeared languages are reinserted into public space through the collective activist work of memory. This happens, too, in the very different context of North America, for instance, where Indigenous languages have begun to reclaim their place in urban space – as place names, as street names, or in museums as messages addressed to new publics. These translations bring into being forms of inclusive and democratic expression.

There is a special character to cities where more than one language group feels a sense of entitlement to the same territory. Both communities consider themselves “insiders” – original or longstanding presences. One thinks of Barcelona with Catalan and Spanish, of Brussels with French and Flemish, of Montreal with English and French and so on. In places where two languages dispute dominance, translation is an explicit form of territorialisation. Buildings, monuments are re-branded. Post-colonial and post-imperial cities display this same struggle for public space, as the emergent vernaculars of the new national powers attempt to recover the symbolic spaces previously occupied by the metropolitan tongue, and as the knowledges embodied in the old languages are marginalized. Often such cities are spatially divided – with areas still marked by the tongues of former powers. Kolkata in English, Bengali or Hindi? Dakar in French or Wolof? New Orleans in French, Spanish or English? Johannesburg in English, Afrikaans or Xhosa? Manila in Spanish or Tagalog? Thessaloniki in Greek or Turkish? Each of these questions brings into being a different constellation of linguistic forces and spatial imaginaries, shaped by histories of conflict, patterns of immigration, diasporic ties, political jurisdictions, emergent or declining cultural loyalties. To move from one language to another is to move across urban space into new frames of interpretation. The city becomes a crossroads of codes, where memories meet at odd angles.

In addition to the broad dynamics of history that define different categories of translational cities, cities can be studied for the specific translation sites that they bring into being. Translation sites are places shaped by language traffic, where languages and histories meet – in modes of coexistence, rivalry or conquest. They are hotels, markets, museums, checkpoints, gardens, bridges and streets, charged with the tension between here and elsewhere, by conversation across languages. The hotel is a site of both transience and rootedness. The Hotel Bristol in Vienna beloved of Joseph Roth, Cees Nooteboom’s Ritz in Barcelona or Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) – these hotels speak the language of community. By contrast, the Tokyo Park Hyatt in Sophia Coppola’s 2003 film Lost in Translation is more like a “non-place” and aligns with weak forms of translation and melancholic indifference. A German opera house in Prague, a “synagogue” called Santa Maria la Blanca in Toledo, the streets of Montreal during a summer of demonstrations, markets like Chungking Mansion in Hong Kong… these are sites of encounter and unresolved exchange. Some translation sites are “disciplinary,” exercising forms of surveillance and control. This is the case for borders, checkpoints or reception centres – like the historic Ellis Island or today’s airports where migrants are processed for entry into national territory.

|  |

Two legendary hotels and translation sites. The Karlovy Vary (l) was the inspiration for Wes Anderson’s Grand Budapest Hotel and the Bristol (r) was the novelist Joseph Roth’s favourite stopping-place in Vienna.

Like translations which display the double realities of which they are composed, translation sites are unsettling; they lay bare the lineaments of difference. Stimulating the imagination, translation sites recall the habit of mind that Anne Carson describes from long years of reading bilingual books. Every page read seems to refer to some forgotten or vanished left-hand original. This is like seeing “two tracks of reality running at the same time.” Illuminations gather in the folds between the pages, offering “two realities for the price of one” (1999, 8). For Carson, “the best connections are the ones that draw attention to their own frailty” (2016).

In their relentless pursuit of the affect of place, writers like W.G. Sebald or Teju Cole wander the streets of cities in pursuit of stories buried beneath the surface. They sift through layers of history, seeking signposts in “an endless apprenticeship of seeing”. They juxtapose odd places and moments, creating flashes of the uncanny. But what of hearing? What of the layered geographies, the shifting territories, of language past and present? These too need their cartographers.

Sherry Simon is the author of Translating Montreal. Episodes in the Life of a Divided City (2006), Cities in Translation: Intersections of Language and Memory (2012) and the forthcoming Translation Sites: A Field Guide (2019).

All essays on Language and the City

Introduction

Rivke Jaffe

City Talk

David Madden

The City and its Languages: Taking Linguistic Diversity Seriously

Virginie Mamadouh

Public Signage: Language, Ideology and Claims to Urban Space

Mieke Vandenbroucke

The Translational City

Sherry Simon

Related IJURR articles on Language and the City

The Return of the Slum: Does Language Matter?

Alan Gilbert

Writing the Lines of Connection: Unveiling the Strange Language of Urbanization

Nathalie Boucher, Mariana Cavalcanti, Stefan Kipfer, Edgar Pieterse, Vyjayanthi Rao, Nasra Smith

Questioning the use of ‘local democracy’ as a discursive strategy for political mobilization in Los Angeles, Montreal and Toronto

Julie‐Anne Boudreau

Toponymy as Commodity: Exploring the Economic Dimensions of Urban Place Names

Duncan Light, Craig Young

© 2019 THE AUTHOR. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF URBAN AND REGIONAL RESEARCH, PUBLISHED BY JOHN WILEY & SONS LTD UNDER LICENSE BY URBAN RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS LIMITED

This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License, which permits use and distribution in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, the use is non-commercial and no modifications or adaptations are made.