On a day like any other, Maggie uses her electronic travel card to catch one of Melbourne’s metropolitan trains. Most passengers load credit onto their cards to access public transport services, but because Maggie has disabilities, she has a disability exemption loaded onto her card. For Maggie, gates open without payment and she uses staffed disability access gates that are kept open for ease of movement. On this particular day, however, a staff member at the gate is especially eager to perform the task of gatekeeper. As Maggie approaches, they shut the gate onto her shin and ask for proof of her exemption. When Maggie contributed this experience to the research project “The Disability Inclusive City”, she concluded: “I limp, but it is not good enough for them”.

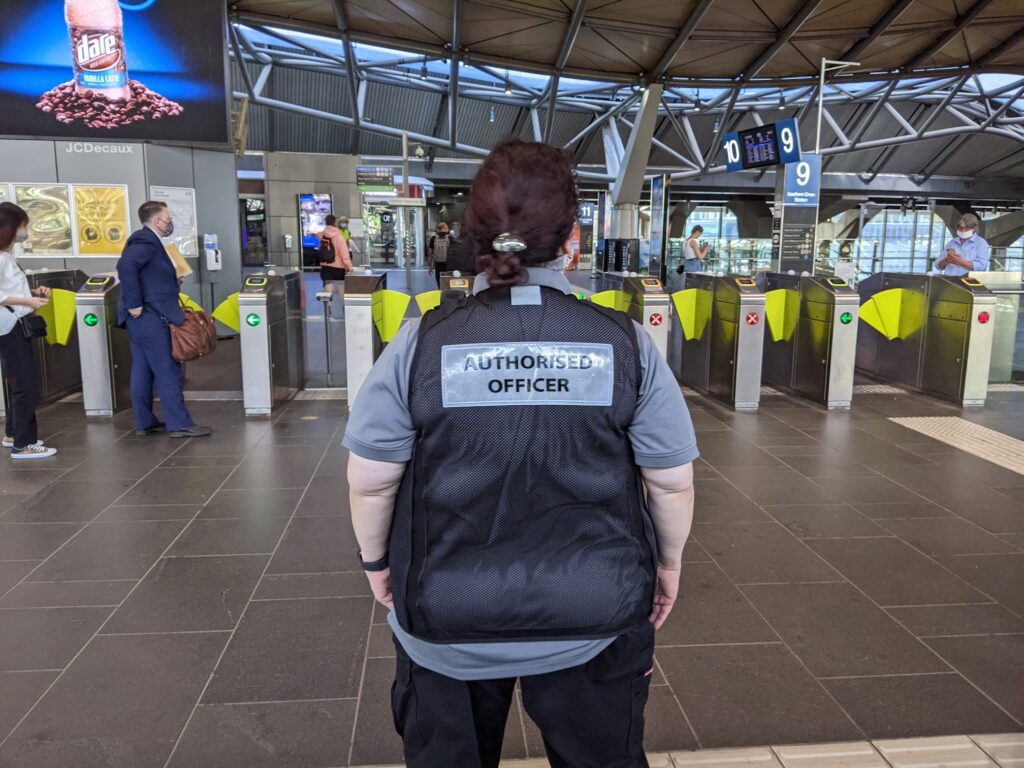

Security officer at Melbourne’s Southern Cross Station, November 2020. Photo: Ellen van Holstein.

Maggie’s experience with gatekeeping is all too familiar for many people with disabilities. As barriers are actively built into urban environments, policy makers and planners often devise access solutions that require people to use alternative access points or request special accommodation. Maggie’s exemption from touching on and off public transport is an example of such a special accommodation. As a result, people with disabilities are regularly forced to disclose their disability in order to gain access to infrastructures, spaces and opportunities. Governance mechanisms that grant and deny access thus normalise able-bodied and able-mindedness and treat the disability category as exception.

Maggie’s story also illustrates her embodied experience and expression of disability. Maggie has multiple disabilities, one of which is an intellectual or learning disability. Her disability makes specific tasks, such as learning to operate new technologies, challenging for her. At the station she came up against staff who expected disability to be visually discernible. They looked for visual evidence of impairment, and overlooked that, for Maggie, remembering to touch on and off and operating the electronic gates pose greater challenges than aspects of her disability that can easily be visually observed. The interactions between Maggie’s experience of disability, her encounter with public transport infrastructure and with dominant imaginaries of disability, illustrate that disabling processes are constructed by, in and through social interactions and that these interactions are embedded in place (Cockain 2014).

The example also illustrates the politics of visibility and disclosure in the everyday politics of disability access. The practices of disclosure that some LGBTIQ people and some people with disabilities have in common have prompted social theorists to draw parallels between these identity groups. Furthermore, both groups – while internally highly diverse – are associated with a normative binary that has been created and enforced through processes of medicalisation, criminalisation and segregation. These commonalities have led social theorists to conceptualise these two forms of difference in tandem. “Crip theory” is a relatively recent addition to the theoretical toolkit of critical disability studies. It was inspired by LGBTIQ practices of coming out as a way to challenge heteronormativity. Where queer theory prompts urban scholars to queer urban spaces by observing and subverting heteronormativity, crip theory encourages scholars to crip urban spaces by unmasking and challenging compulsory able-bodiedness. In his contribution to this scholarship, Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability, Robert McRuer (2006) argues that like LGBTIQ-identifying people, people with disabilities and their allies can embrace disability as a desirable source of cultural meaning.

The queer liberationist practice of coming out is central in crip theorists’ understanding as a generative political practice that makes disability discernible and that opens up opportunities for celebration. Crip theory and practice encourages sustained forms of coming out as a strategy to free the disability category and identity from stigma and enact a more accessible world (McRuer 2006). McRuer builds on the work of Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, who suggests that the disability category is visually made and maintained through the practice of staring. In her essay “The Politics of Staring: Visual Rhetorics of Disability in Popular Photography”, Garland-Thomson (2002) highlights the uneven power dynamic that is encapsulated in this practice. To challenge this power dynamic, crip theory celebrates expressions of disability that break with stigma and embarrassment and that turn disability into a positive cultural signifier.

People with disabilities are an incredibly diverse group consisting of people with many different kinds and intensities of disabilities, intersectional identities and uneven access to support. Crip theory attempts to encompass the experiences of all people with disabilities, but it prioritises some disability experiences over others. The word ‘cripple’ refers explicitly to the physically impaired and flattens the diversity of lived experiences into a monolithic impairment (Bone 2017). The theory has received critique for this reason, and also because the theory was not developed from within communities of people with disabilities.

The theory’s understanding of coming out as a radical, liberationist practice overlooks that for many people with disabilities, coming out is not a choice. Some people with disabilities do not have the option to pass as able-bodied or able-minded, and people are routinely forced to disclose disability to protect their rights and to gain access to support to which they are entitled. Furthermore, people with intellectual disabilities are often outed by others, which places the advantages of urban anonymity – and the choice to leave the disability closet – beyond their reach. Setting out to crip urban studies might thus come with the risk of leaving some people with disabilities behind. For this reason, I put forward the conceptual framework of the taskscape as an alternative theoretical frame that can ignite urban studies’ engagement with experiences of disability in cities.

The concept of the taskscape was introduced by Tim Ingold (1993) to describe how a landscape forms over time as people’s practices become inscribed in it. Ingold defines a task as “any practical operation, carried out by a skilled agent in an environment, as part of his or her normal business of life” (1993: 158). Ingold stresses that tasks are not performed in a vacuum, and that “every task takes its meaning from its position within an ensemble of tasks, performed in series or in parallel, and usually by many people working together” (1993: 158). Ingold describes an “interlocking” of tasks to foreground that people, in the performance of their tasks, also attend to one another. Ingold refers to such an ensemble of tasks, its technical practices and social activities, as a taskscape. Ingold’s taskscape offers urban studies the opportunity to appreciate people’s profound interdependency and to position this interdependency not as a sign of vulnerability, but as the product of a collaborative, city-making effort.

Cities are complex and demanding environments that lend themselves well to the theoretical perspective of the taskscape. Many urban scholars – for example those with interests in technological innovation (van Holstein et al. 2020), encounters across difference (Koch and Miles 2020) and the emergence of the gig economy (Bissell 2020) – confirm the increasing complexity of managing one’s mobility, employment and social relationships in contemporary cities. The flipside of the flexibility that is made possible by just-in-time technologies is that they demand an ability to respond almost constantly to changing circumstances and prompts in urban environments. For this reason, traveling with an electronic payment card is easier for people who have access to a fully functional, up-to-date smartphone that connects their travel card to their bank account at the push of a button. While systems become more complex, social relationships and communities that support people to adapt to such a dynamic landscape have come under increasing pressure. As urban services are privatised and work conditions are made increasingly precarious, many people with an intellectual disability report high turn-over of their personal support staff and are also likely to encounter new staff in services they regularly use.

Entrance gates at Melbourne’s Southern Cross Station, November 2020. Photo: Ellen van Holstein.

Adopting the lens of the taskscape to understand the experiences of people with disabilities reveals that cities demand new skills and capabilities of residents as the urban environment and its social configurations continuously evolve. The digitisation of transport infrastructure and the installation of electronic gates place a demand on people such as Maggie to learn to operate new technologies. Similarly, changes in approaches to staffing that result in turn-over of staff and lags in staff’s disability awareness training create additional tasks for people such as Maggie to perform, such as disclosing and explaining disability. Each additional task comes with the risk of a gap between the skills and resources demanded by that task and the ability of a person with disability to meet those demands.

The concept of the taskscape aligns closely with the work of urban scholars who have sought to understand cities as socially produced spaces. The concept adds a focus on mundane activities and the skills, technologies and social relationships these require to work in urban studies that foregrounds material access barriers in cities. A taskscape perspective recognises that cities are never finished; they are perpetually formed by ensembles of tasks that become materially inscribed in urban landscapes to create new tasks. Like anyone else, people with disabilities are challenged to respond to new tasks with strategies to tackle them. Such strategies can include using assistive technologies, employing support staff or practising new routines with mentors. Depending on people’s disabilities and their personal preferences, disclosing disability can be part of such strategies but disclosure is not evenly available as a choice. The taskscape offers urban scholars opportunities for developing an enabling theory for the city that breaks away from the hierarchy inside communities of people with disabilities that has tended to privilege sensory and mobility disabilities over other, less discernible expression of disability.

Ellen van Holstein is a research fellow at the University of Melbourne. Her research focuses on technologies and practices that create inclusive urban spaces.

All essays on The Disabling City

Introduction: The Disabling City

Rivke Jaffe

Crip Mobility Justice: Ableism and Active Transportation Debates

Aimi Hamraie

Disability and the Pursuit Of Mobility: Risks And Opportunities in the Indian Urbanscape

Renu Addlakha

The City as Taskscape: An Enabling Theory for the City

Ellen van Holstein

Geographies of Security and Disabled People’s Urban Lives

Claire Edwards

Related IJURR articles on The Disabling City

Urban Citizenship, the Right to the City and Politics of Disability in Istanbul

Dikmen Bezmez

© 2020 THE AUTHOR. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF URBAN AND REGIONAL RESEARCH, PUBLISHED BY JOHN WILEY & SONS LTD UNDER LICENSE BY URBAN RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS LIMITED

This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License, which permits use and distribution in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, the use is non-commercial and no modifications or adaptations are made.