Rodents, and subsequently cats, have long been entangled with humans. All domestic cats (Felis catus) are descended from a Middle Eastern lineage of wild cat (Felis sylvestris libyca), suggesting that their domestication originated in the fertile crescent about 10,000 years ago. Grain storage in early human agricultural settlements would have attracted the first commensal rodents, and the cats that came in after them would have been tolerated and welcomed as useful ‘rodent exterminating operatives’.

Domestic cats are also valued human companions (their ‘cute’ large eyes, flattened faces and high round foreheads are characteristics known to promote nurturing behaviour in humans). The role of cat as an indoor pet is relatively recent, facilitated by urbanization and developments in parasite control and cat litter products after the Second World War. Yet a 9,500-year-old grave in Cyprus contains the remains of a human and a domestic cat, each lined up facing west, suggesting that cats had already by this time become imbued with symbolic, and perhaps emotive, significance.

The spread of humans, along with their domestic animals, altered the ecology of the Earth. In this age of the Anthropocene, the biomass of humans is 8.5 times higher than all wild land mammals combined, and the biomass of livestock (mostly pigs and cattle) is 14 times higher. There are an estimated 600-750 million domestic cats globally, placing significant pressure on rodents and other small wildlife). Widespread use of rodenticides against pest rodents threatens biodiversity yet further because of the dangers it poses to non-target animals and in causing secondary poisoning of wild scavengers and predators.

How human society manages the dilemmas posed by this multi-species entanglement of humans, commensal rodents, cats and wildlife is a matter of what Haraway calls ‘cosmopolitics’, over which ‘historically situated practices of multi-species living and dying should flourish’. This paper provides three case studies of such cosmopolitics in the city of Cape Town, showing how practices are shaped by rival worldviews and political-economic factors.

The contested ethics of rodent control in a working-class suburb

In 2013/4, environmental officials in Khayelitsha, a working-class suburb of Cape Town, devised a novel approach to dealing with a burgeoning rat problem. Concerned about the environmental impact of rodenticides, they hired unemployed people to catch and drown rats. This initiative proved popular but was halted after the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA) insisted it was cruel and illegal to drown captured rats.

The Khayelitsha officials defended the program arguing that drowning was more humane for the rats than poison – and safer for children and non-target animals. Evidence was on their side: rodenticides cause protracted, painful deaths; and in Cape Town, rodenticides have been found in the bodies of every species of predator and are known to have poisoned children. The SPCA, however, argued that poisoning pest rodents was legal (even if cruel), while drowning rats could encourage people to drown other animals and even children.

The anti-animal cruelty movement, which sought to provide unwanted and ‘stray’ animals a humane death, originated in Victorian cities as part of the broader social reform movements. Teaching people to treat animals humanely was thought to benefit animals and reduce antisocial behaviours such as the drunkenness and rowdiness that frequently accompanied animal baiting. The Cape Town SPCA’s concern about social messaging is suggestive of a similar civilizing mission towards poor people as well as a (very colonial) predisposition to impose their understanding of animal welfare on others.

Cultural constructions and rival approaches to animal cruelty were at play in this cosmopolitics about animal and human welfare. But this was not, primarily, a clash of values: it was a raw exercise of power on the part of the SPCA. Faced with the threat of legal action it could not afford, the Khayelitsha municipality abandoned the job creation program and reverted to rodenticide use.

Cats as predators and prey

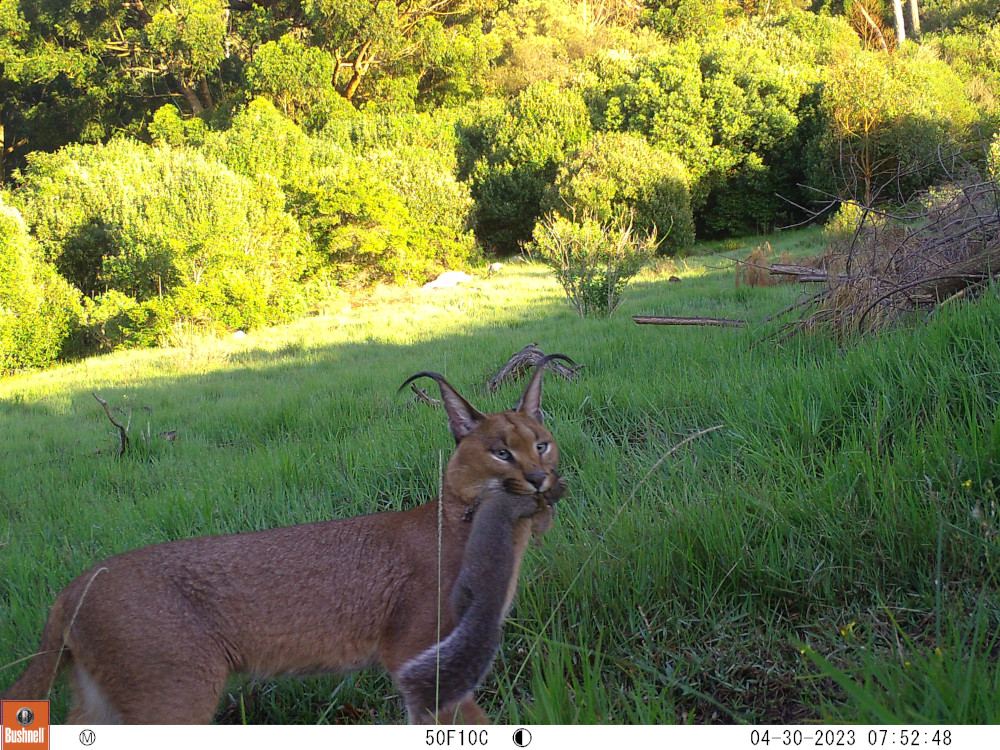

In 2016/17, residents of the up-market Atlantic Beach Golf Estate in peri-urban Cape Town locked horns over the liberties and protections afforded pet cats. Free-ranging domestic cats in Cape Town are estimated to kill 27.5 million small animals every year. They do, however, sometimes fall prey themselves to wild caracals (Caracal caracal), the largest of the small felids. Caracals are not an endangered species, but the small population in and around Cape Town is a vulnerable and treasured wildlife asset. Thus when a visiting caracal started killing cats on the Estate, conflict erupted over which animal was to be protected.

Those already annoyed by the predatory impact of cats on the local wildlife hailed the caracal as a purveyor of cosmic justice. Cat owners, however, decried the ‘murder’ of their ‘fur children’ and demanded that the caracal be captured and removed. A survey of residents revealed that a clear majority favoured leaving the caracal alone and that pet cats be kept on the private property of their owners. Wildlife officials refused requests to remove the caracal and the matter was resolved only when the caracal was killed on a nearby highway.

The dispute was very much a bourgeois cosmopolitics about what it means to live with nature (albeit in a highly curated version). But it was also a cosmopolitics about the role of cats in human society – a problem that cuts to the heart of the animal rights movement. In their extension of political philosophy to animal rights, Sue Donaldson and Will Kymlicka conceptualise domesticated animals as ‘co-citizens’ with rights to flourish but also obligations not to do so at the expense of others. Wild animals, by contrast, are like citizens of a foreign sovereign nation, free to follow their own rules including eating other animals. Feral and commensal animals are conceptualised as ‘liminal’ animals living within human spaces and therefore subject to some constraints but generally left to their own devices. Donaldson and Kymlicka acknowledge that domestic cats pose a challenge to this citizenship model because, as obligate carnivores, they cannot flourish within harming others and thus cannot be co-citizens. Cats could, alternatively, live feral/liminal lives, but Donaldson and Kymlicka are wary of this too because of the known impact of cats on small wildlife.

Liminality is a concept initially used in anthropology to denote ‘betwixt and between’ social states, such as the transition from child to adult. It has more recently been employed in ‘more-than-human’ ethnography and animal studies to refer to betwixt and between states within human-animal entanglements. Cats are quintessentially liminal in the way they traverse and cross domestic and wild spaces, and in the shifting categories we impose on them. Depending on context, cats are cossetted family members (‘fur children’), admired independent rodent killers (‘rodent exterminating operatives’), despised ‘invasive’ predators of endangered wildlife, appreciated ‘community cats’ or persecuted ‘nuisance’ ‘feral’ creatures. When ‘stray’ and ‘rescued’ by animal welfare organizations, they enter a precarious liminal state as pets-in-waiting whose destination is either a ‘forever home’ or ‘euthanasia’.

In some contexts, ‘feral’ cats are euthanized immediately, though how to tell the difference between a feral and a stray cat is contested and often ad hoc. Sometimes feral cats are neutered and ‘returned’ to live additionally liminal lives in partially provisioned colonies as neither functionally wild nor fully cared for. For People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), this is an unacceptable act of animal abandonment. For other animal welfare organisations, including the Cape Town SPCA, it is a practical as well as humane solution. How these rival world views play out is a matter of historical path dependency – notably the longstanding authority and influence of the SPCA and of local cosmopolitics.

The contested ethics of feral cats on Cape Town’s urban edge

The Cape Town SPCA euthanizes unadoptable ‘stray’ cats but endorses the ‘trap-neuter-return’ of feral cats living in partially provisioned urban colonies. It acknowledges that feral cats lead a ‘dangerous and difficult existence’ but nevertheless recommends that businesses and factories keep a ‘small and manageable colony as they assist with keeping rodent populations down and other cats at bay’. That free-ranging cats also impact wildlife is simply ‘acknowledged as part of the dynamic of dealing with feral cats’. Such a ‘dynamic’, however, can pose serious dilemmas for biological conservation on the urban edge – as revealed recently by a study at the University of Cape Town (UCT).

UCT’s upper campus, which juts into Table Mountain National Park, is home to two small colonies of neutered, semi-feral cats. Recent camera trap surveys of wildlife on and around the upper campus revealed the presence of small antelope, caracals, small predators (genets, mongooses), raptors, rodents and cats. The domestic cat was by far the most abundant species. Many images of cats with prey were captured, including coming into campus from the National Park (Figure 1 and 2). Their prey included indigenous rodents and birds as well as exotic species, such as the grey squirrel, pigeons and invasive rats.

A cat returning from the National Park with a rodent. Source: Wildlife survey by Zoë Woodgate (2022/2023).

Cats returning from the National Park with a rodent. Source: Wildlife survey by Zoë Woodgate (2022/2023)

Caracal. Source: Wildlife survey by Zoë Woodgate (2022/2023).

A grey cat provisioning kittens with wild prey and kitchen refuse. Source: Wildlife survey by Zoë Woodgate (2022/2023).

A grey cat provisioning kittens with wild prey and kitchen refuse. Source: Wildlife survey by Zoë Woodgate (2022/2023).

Poorly managed refuse at UCT which encourages rats and attracts cats. Wildlife survey by Zoë Woodgate (2022/2023).

Rodent. Source: Wildlife survey by Zoë Woodgate (2022/2023).

The camera-trap surveys have been useful in exploding several myths held by cat-carers, notably: that human-provisioned cats do not hunt; that neutered colony cats do not stray beyond small territories; and that all cats on campus are known. This, and the revealed presence of caracals (Figure 3), was helpful in initiating a discussion of how to care for cats and wildlife on campus. Caracals pose a threat to free-ranging cats (and probably account for the disappearances of several known colony cats). Cats, however, also pose dangers to caracals, as they could potentially spread diseases to them when taken as prey. Campus cats have tested positive for Feline Immunodeficiency Virus in the past and several kittens are known to have died from Feline Herpes Virus (the ‘snuffles’).

The camera trap surveys also highlighted the long-standing multi-species entanglement of humans, rodents and cats. The images included here show how domestic cats scavenge in and around overflowing rubbish bins (poorly managed food waste outside university residences also provides a perfect environment for rats). This situation is the result of persisting financial constraints, managerial challenges and poor recycling behaviour across the university community. It illustrates the complexities and cosmopolitics involved in moving from normative support for ecological sustainability to practical measures that reduce waste and the need for rodenticides on campus.

Conclusion

Cosmopolitics about cats, rats and wildlife in Cape Town is revealing of conflicting world views and socio-economic inequality. Residents in an upmarket eco-estate had the luxury of debating which animals belonged in their privileged curation of nature, even as they argued over the rights of cats. The SPCA was variously uncompromising in its dealings with a working-class community, accommodating towards feral cats in commercial areas, and effectively unconcerned about wildlife in both cases. There is emerging consideration of the impact of feral cats and rodenticides on wildlife, but even in the most promising context for dealing with this – a world class university on Cape Town’s urban edge – solutions remain elusive.

Ecologists hope that by ‘raising awareness’ about animal lives and the pressures humans place on them, the tide will turn in favour of more ecologically sustainable outcomes. Information, however, is always filtered by conflicting interests/passions (people can love cats and wildlife). At best, awareness of the trade-off concerned can help shape the relevant cosmopolitics over which creatures are allowed to flourish – but this too will be framed and constrained by economic and institutional interests and considerations.

Prof Nicoli Nattrass is a development economist in the School of Economics at the University of Cape Town (UCT) with an inter-disciplinary background in social science. She is the co-Director of the Institute for Communities and Wildlife in Africa (iCWild). Nicoli won the UCT teachers award in 2001 and has twice won the UCT book award: in 2005 for ‘The Moral Economy of AIDS in South Africa’, and in 2014 for ‘The AIDS Conspiracy: Science Fights Back’. Her recent work focuses on the interface between science and society and human wildlife conflict.

Zoë Woodgate is a postdoctoral researcher at Institute for Communities and Wildlife in Africa (iCWild). She obtained her PhD in 2022, in which she identified key drivers of species’ distribution across the Karoo region of South Africa. Currently she focuses on using novel methods to investigate population threats for mammals, to ultimately inform conservation mandates.

All essays on Animals and the City

Introduction: Animals and the City

Rivke Jaffe

On More-than-human Public Space: Kabootar Chowk in Karachi

Aseela Haque

Affective Geographies: Managing Feral Cat Colonies in Rome

Giovanna Capponi

Urban Animals: Bison on Display, and the Grand Temporal and Geographic Scales of Urbanization

Dawn Biehler

The Metropolis and Metabolic Life

Maan Barua

Zoonotic Urbanization

Matthew Gandy

Cats, Commensal Rodents and Cosmopolitics in Cape Town

Nicoli Nattrass & Zoë Woodgate

Published online February 2024

Related IJURR articles on Animals and the City

Weeds, Pheasants and Wild Dogs: Resituating the Ecological Paradigm in Postindustrial Detroit Paul Draus and Juliette Roddy

The Zoonotic City: Urban Political Ecology and the Pandemic Imaginary Matthew Gandy

Rethinking Urban Epidemiology: Natures, Networks and Materialities Meike Wolf

Of Holy Cows and Unholy Politics: Dalits, Annihilation and More-than-Human Urban Abolition Ecologies Rajyashree N. Reddy

© 2024 THE AUTHOR. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF URBAN AND REGIONAL RESEARCH, PUBLISHED BY JOHN WILEY & SONS LTD UNDER LICENSE BY URBAN RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS LIMITED

This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License, which permits use and distribution in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, the use is non-commercial and no modifications or adaptations are made.