Sara Gebremeskel’s PhD research, which in its writing-up phase was supported by the IJURR Foundation, has yielded groundbreaking insights into the urban dynamics of Mekelle, Ethiopia. In this blog post she aims to shed light on the most significant findings from her research and the future direction it will take.

Vibrant pedestrian presence and activity

One of the most remarkable findings from my research is the vibrant pedestrian presence in Mekelle. Over 52% of the city’s population actively engages in walking, with an average speed of 1.34 m/s. Pedestrian activity constitutes 67.83% of the overall street activity, primarily driven by necessity. These statistics underscore the vital role walking plays in the daily lives of Mekelle’s residents, highlighting the city’s active pedestrian environment.

Infrastructural deficiencies hindering pedestrian flow

Despite the high levels of pedestrian activity, my empirical model uncovered several infrastructural deficiencies that significantly hinder pedestrian flow. Some key issues include:

• Lack of properly networked sidewalks: fragmented and poorly maintained sidewalks pose safety risks and disrupt the smooth flow of pedestrian traffic.

• Inadequate lighting: insufficient street lighting reduces visibility and safety, particularly at night, further discouraging walking.

These findings emphasize the urgent need for infrastructural improvements to enhance pedestrian safety and mobility in Mekelle.

Behavioral resistance and urban design insights

A fascinating aspect of my research examines the dynamic interaction between pedestrians and their urban environment. Beyond ordinary infrastructure needs, various forms of behavioral resistance have emerged, revealing how pedestrians adapt to their surroundings.

• Ignoring crosswalks: Most pedestrians choose to cross streets at non-designated points, indicating a disconnect between infrastructure design and user behavior.

• Navigating in undefined patterns: Over 50% of pedestrians walk off-sidewalks, navigating through unconventional routes often dictated by the inefficiencies of the existing infrastructure.

These seemingly disruptive actions offer valuable insights into urban design and planning. By understanding these behaviors, urban planners can develop targeted design interventions to enhance pedestrian experiences and overall urban functionality.

Introducing “Merebatatstreet“: a context-led urban design theory

Building on these insights, my research introduced a context-led urban design theory called “Merebatatstreet*.” This theory aims to reclaim streets by considering the place attachment profile of society with their “mereba” (social space). The Merebatatstreet concept focuses on creating multifunctional spaces and fostering a sense of shared responsibility for place management. It promotes the traditional features of mereba in street design, providing spaces with centrality, communality, and multifunctionality. These spaces encourage social gathering, a strong sense of community, and inclusivity, regardless of age, gender, status, or physical ability. They also serve as platforms for everyday activities, social manners, conflict resolution, and communal support. By interpreting these features alongside urban insights, five guiding principles are developed to translate the Merebatatstreet concept: flexibility and context-sensitivity, practicability for everyday use, multifunctionality, collective ownership of public spaces, and inter- and intra-connectivity at the street level.

Merebatatstreet typologies and street experiments

The study proposed 18 street experiment models that guided the development of four distinct street typologies based on their primary function: Access Street, Market Street, Entertainment Street, and Social Street. These typologies reflect Merebatatstreet concept, promoting a variety of functional arrangements throughout a day and fostering cultural contacts and identity. They also enhance inter-street and intra-street connectivity, improving overall accessibility. The street typologies have been adapted to the existing mono-centric feature of the city but offer even greater potential if the city develops within a polycentric framework. This introduces a novel urban design approach that has not yet been considered by local planning tools. This study has illustrated the sections of the street typology models using a web app streetplan.net**. It has considered standards of the Ethiopian urban street design manual (ITDP & UN-Habitat, 2023) and global standards that are integrated in the web app.

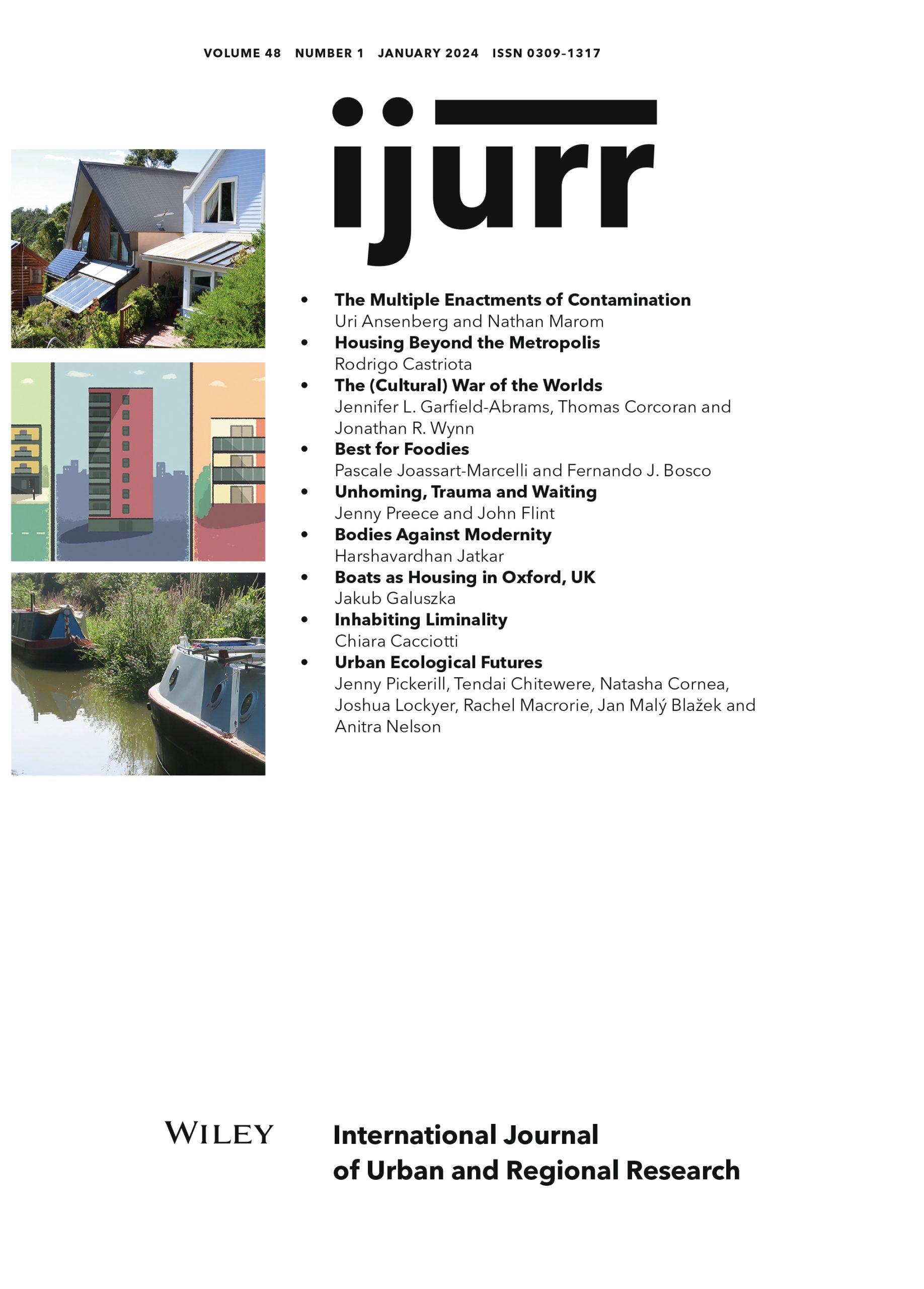

1. Access street typology

This typology can be implemented in sub-arterial streets, which serve as public transport routes connecting sub-cities. Its primary functions include providing access for public transport, walking, and cycling. It can be applied as a single street in the last mile to and from origins and destinations, and on a district scale to encourage public transport use and reduce traffic congestion at centers. To further amplify its impact, this street typology can also be implemented on a city scale. Key street experiment models include converting shop extensions to window shopping, creating walking spaces, providing dedicated bus and bike lanes, and ensuring crossings along desired lines.

Figure 1: section of access street typology.

Figure 1: section of access street typology.

Two-way bus lane with 40km/hr speed limit, both side bike lane, dedicated sidewalk on both

sides buffered by green strip (street tree, seating, street vending activities and transit shelter)

and a median buffer (with spots for crossing pausing activities). Source: the author, 2024.

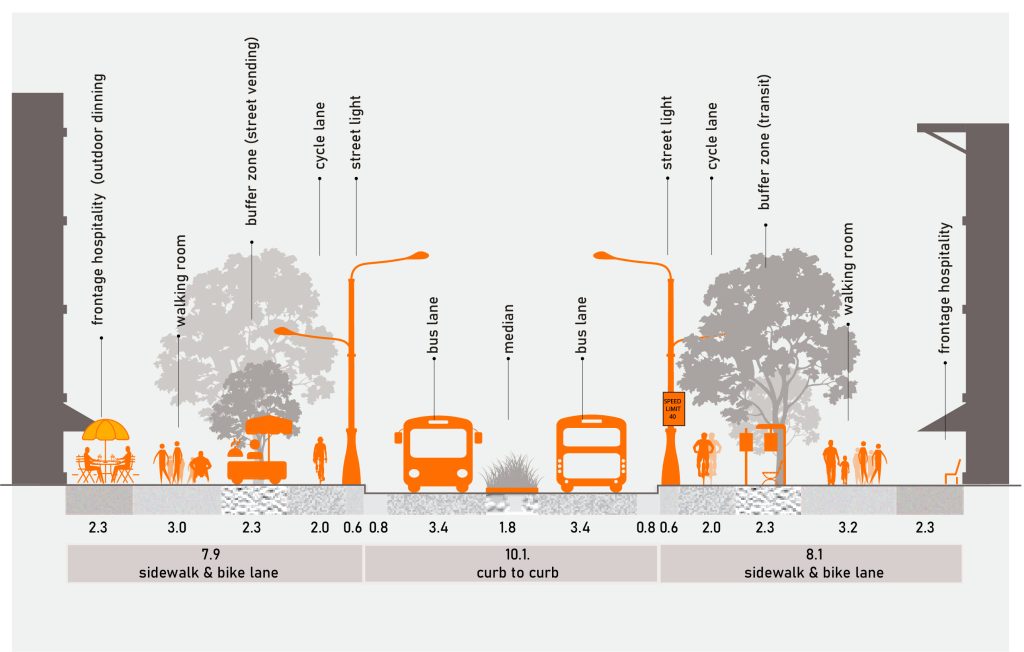

2. Market street typology

This typology is ideal for market areas, promoting street marketing activities involving street vendors. It serves as linear infrastructure for street marketing, integrating vendors into planning and design. Defined through partnerships, as seen in several African countries, it can avoid forced formalizations, relocations, or demolitions. The typology can be applied in collector streets and implemented as a single street in the last mile to market areas or at the marketplace scale, providing pedestrian-friendly zones. Street experiments related to this typology include designating curbsides for vendors and creating platforms for on-street marketing.

Figure 2: street section of Market Street typology.

Figure 2: street section of Market Street typology.

One way car lane with 30km/hr. Speed limit, one side two-way bike lane, dedicated sidewalk

in both sides buffered by green stripes (street tree, street food and street seating on one side

and street shop, street tree, street seating on the other side)

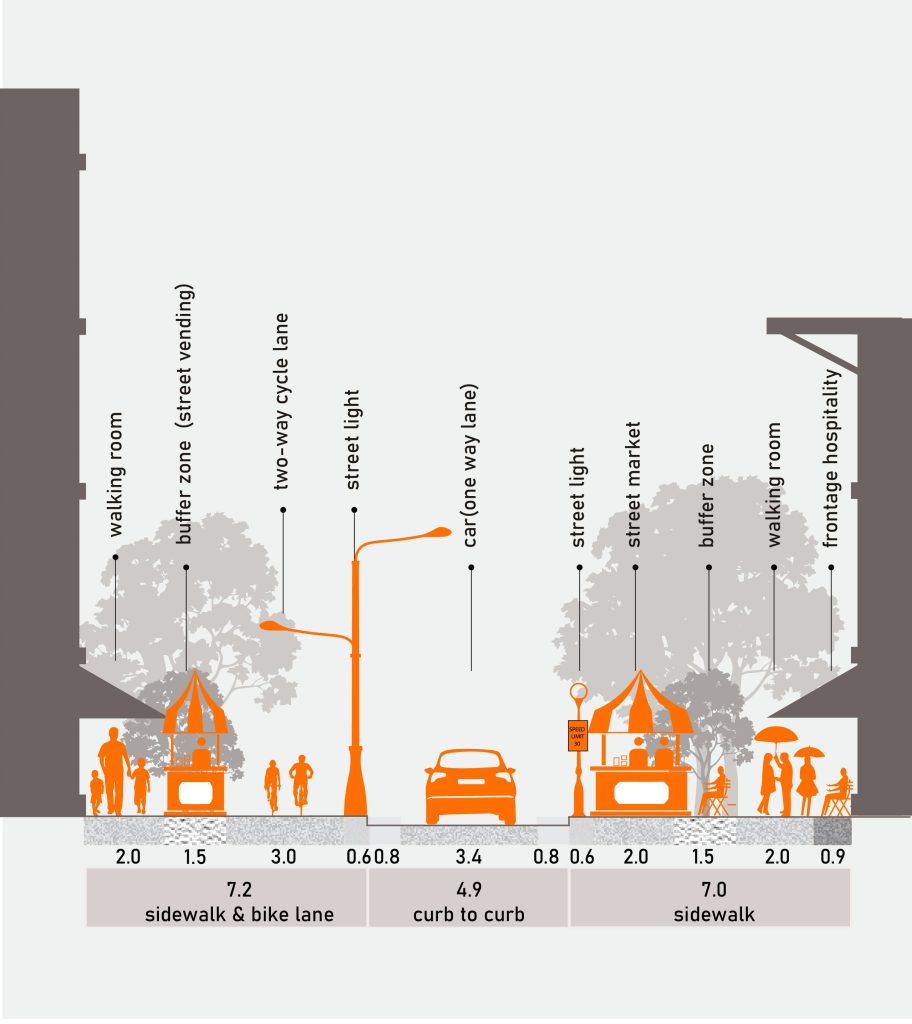

3. Entertainment street typology

This typology is suitable for local routes in the last mile towards schools, public places, and residential areas. It is a fully pedestrian street, promoting safe routes to school and residential areas, especially for children. It also provides access to nearby public places for the elderly and those with mobility disabilities to enjoy outdoor activities. This typology can be applied as a single street in the last mile to schools and residential areas or on a neighborhood scale as a pedestrian zone to enhance social interaction. A key street experiment is providing on-street entertainment platforms.

Figure 3: section of entertainment street typology.

Figure 3: section of entertainment street typology.

Shared sidewalk on both sides buffered by street tree and green strip in one side and by street

tree, outdoor dining and street seating on the other side. Shared lane with platforms for

entertainment such as play and exercise activities.

4. Social Street typology

Focusing on facilitating social gatherings and promoting social life, this full pedestrian street enhances city life. It is suitable for local routes in the last mile towards city destinations such as heritage sites and landmarks, providing safe access and platforms for cultural activities. This typology can be applied as a single street in the last mile to destination areas or on a district scale as a pedestrian zone to foster social interaction. Street experiments related to this typology include creating platforms for social life, frontage hospitality, and sidewalk pausing spots for momentary interactions.

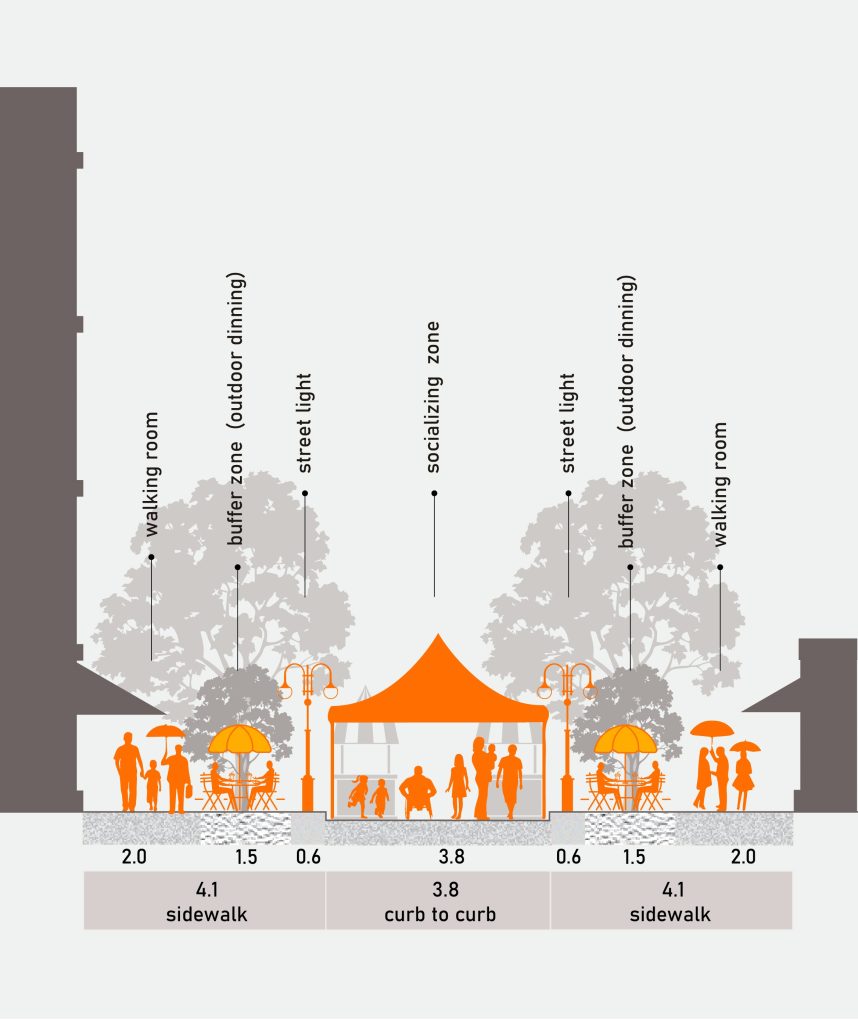

Figure 4: Section of social street typology.

Figure 4: Section of social street typology.

Frontage hospitality zone on one side, shared sidewalk on both sides buffered by street tree,

outdoor dining and street seating. Shared lane with platforms for socializing activities.

Strategic frameworks for reimagining urban streets

To translate the vision of creating richer urban experiences into practice, my research proposed strategic frameworks with actionable strategies. These frameworks serve as a roadmap for implementing the Merebatatstreet concept and evaluating its performance. The monitoring and evaluation framework identifies impacts and areas for improvement based on the implementation of proposed interventions. This evaluation design explores primary goals, expected outcomes, indicators, and evaluation questions for each street experiment model, facilitating comparisons using before-and-after intervention data.

Taking the research forward: new directions and insights

Upon completing my PhD, I aim to expand these foundational findings, exploring new directions and gaining further insights. Focus areas include:

1. Expanding urban design theories: investigating the applicability of the Merebatatstreet theory in diverse urban contexts and refining its principles through engaging in postdoctoral research and project calls.

2. Collaborative research and innovation: partnering with urban planners, architects, and policymakers to develop innovative urban design solutions. I have networks with organizations such as Clever Hybrids, GSTS, the Gendered City, GWCN, Think Africa City, VREF, Walk21, Cities & Health, the Future Design of Streets, GDCI, and UNHabitat.

3. Organizing workshops: conducting real-life experiment workshops on proposed urban design interventions to showcase their practicability.

4. Evaluating impact: conducting longitudinal studies to assess the long-term impact of the proposed urban design interventions on pedestrian behavior, safety, and urban livability.

Further insights from ongoing research highlight the importance of a context-led approach to urban design, addressing both infrastructural deficiencies and behavioral patterns to inspire innovative solutions for more pedestrian-friendly cities.

Conclusion

The support from the IJURR Foundation has been pivotal in advancing my research and enabling valuable contributions to urban design and planning. By understanding and addressing the dynamic interactions between pedestrians and their urban environment, my research aims to inspire innovative solutions that enhance urban livability and create richer urban experiences. The journey continues, with a commitment to reimagining and transforming urban streets for the better.

*combined word of Tigrigna words ‘merebatat’ (multiple mereba) and a street. The word mereba comes from the Tigringna language and means “center” or “middle.” Mereba plays a significant role in Tigrayan housing culture. It is a communal space found in the center of a traditional Tigrayan compound, typically consisting of a circular or rectangular courtyard surrounded by several dwellings (Shimizu et al., 2019).

**StreetPlan.net is a free web-based drag & drop tool for illustrating design ideas based on best practice guidance from “Designing Walkable Thoroughfares” a joint publication of the Institute of Transportation Engineers and the Congress for New Urbanism (ITE and CNU). It also includes templates designed by NACTO. https://www.cdn.streetplan.net.

Sara Gebremeskel

Mekelle University, School of Architecture and Urban Planning

PhD Candidate, Università Iuav di Venezia