Housing cooperatives and Community Land Trusts are innovative forms of social organization that emerge in response to the limitations of both state and market. Matthew Thompson’s Reconstructing Public Housing: Liverpool’s Hidden History of Collective Alternatives is a richly detailed political history of the struggle for de-commodified housing in one city. It traces the rise, fall and reconfiguration of the cooperative ideal through an in-depth case study of housing politics in the northern English city of Liverpool.

Deindustrialization hit Liverpool early and hard. As the city’s population decreased and its economic base weakened, the substantial housing stock fell into disrepair. Reconstructing Public Housing recounts the fight for affordable housing through a series of struggles that produced institutional innovations. The housing cooperative movement emerged in the late 1960s and drew on existing practices and resources such as the self-build movement, anarchist-inspired squats, the non-profit sector, and government funding for low-income housing. Local residents mobilized against slum clearance programmes and the poor-quality high-rise buildings that came in their wake. In the 1970s, the Shelter Neighbourhood Action Project (SNAP) spearheaded a movement to rehabilitate rather than demolish inner-city neighbourhoods and became an incubator—then a flagship project—that demonstrated how resident participation could lead to the co-production of liveable urban space.

The conservative national government, which was searching for a new alternative to council housing, introduced the enabling legislation for collective tenure, but initially insisted on the less socialist-sounding term ‘co-ownership’. Although it faced a ‘Byzantine local bureaucracy’ (p. 67), SNAP kick-started the cooperative movement in Liverpool and co-founded Neighbourhood Housing Services, an organization that developed significant capacity to train members, work with local governments and support new co-ops. With these pieces in place, the movement was in a good position to benefit from financial support for urban renewal.

In the 1980s, a stalemate emerged at the national level between the Liberals, who criticized a sclerotic and costly public sector bureaucracy, and the Labour Party, which defended the unionized public sector workforce. New building became more difficult, and what limited support there was for new housing co-ops came at the expense of investment in the construction and maintenance of public housing. This set the stage for the surprising twist in the story, when at the local level the far-left dominated Labour Party came to power in Liverpool, led by the ‘Militant Tendency’ (p. 90). Liverpool City Council introduced a debt-funded ‘Urban Regeneration Strategy’ (p. 105) centred around public housing and withdrew support for housing co-ops, which the new administration described as elitist and exclusive. In the end, it was a left-leaning Labour local administration—not a conservative one—that was responsible for refocusing housing policy away from the vision of an earlier generation of anarchists and communitarian-socialists, who saw cooperatives as a way to combine freedom with democratic governance.

This brief overview is insufficient to capture the full scope and detail of this fascinating account, which effortlessly weaves together urban theory, political history and a social-movement-inspired approach to social change. Nonetheless, this is a book with wide appeal beyond readers who are interested in Liverpool and/or the history of housing cooperatives. The first chapters provide a genealogy of critical urbanist ideas about commoning, self-build housing and participatory architecture. Thompson places the issue of housing in the context of broader discussions about dwelling, community-building and place-making. While some of these concepts have been taken up in the professionalized, technocratic and performative side of planning, Thompson foregrounds social movements and connects his analysis with a broader structural understanding of capital accumulation and dispossession.

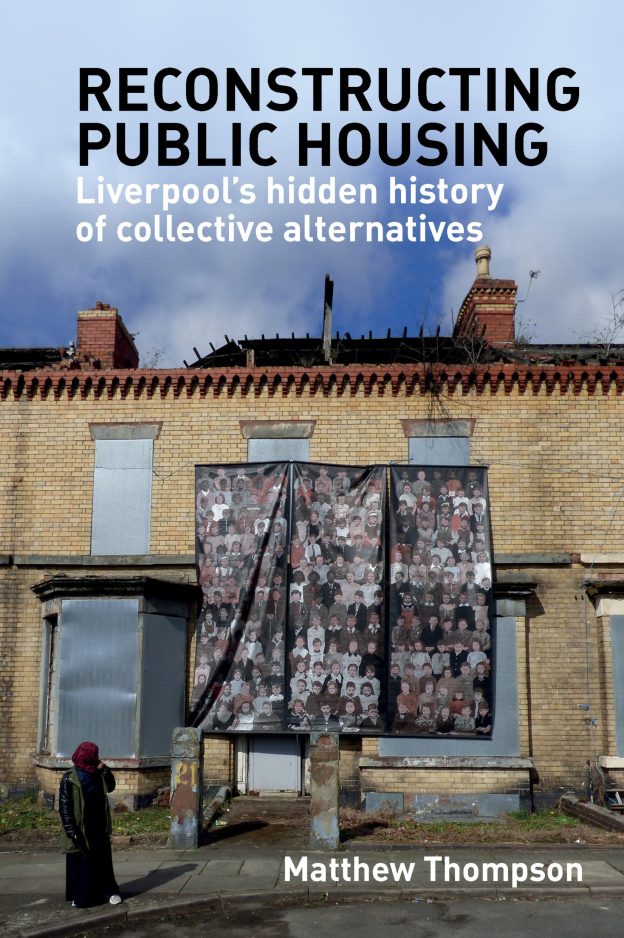

The book is encyclopaedic in its treatment of collective housing in Liverpool, and the final chapters bring the story up to the present with a discussion of Community Land Trusts. There is a fascinating discussion of Assemble, a group of activist-architects who became famous after they won the Turner Prize in 2015 for their work on Granby 4 Streets. Their goal was not only to turn 27 boarded-up properties into refurbished affordable housing, but also to foster ‘a hands-on’ mode of delivery that built on the community’s enterprise and initiative by maximizing participation in the construction project. This collective homesteading was intended to boost the local economy while also giving local people a way to shape its development (p. 222).

The question that drives the book is less the empirical puzzle—what caused these collective alternatives to flourish in Liverpool when they did—and more the theoretical one. Was Friedrich Engels right that the utopian plans of bourgeois reformers are ‘isolated solutions’ that are doomed to fail as long as the capitalist mode of production flourishes? Thompson argues that these alternative ways of dwelling show how urban space can be remade collectively and can dominate exchange. He beautifully describes them as ‘openings in the ideological fabric that wraps our own world in a veneer of inevitability’ (p. xviii).

For Thompson, the goal is not just the provision of decent housing but also the creation of a less alienating and more fully human practice of dwelling (p. 252). He sees signs of this movement in the real utopias being constructed in Liverpool and elsewhere and in the platforms of political parties such as Podemos in Spain and the British Labour Party. The new municipalism in Barcelona is another successful illustration of the renewed emphasis on community control. According to Thompson, the capillary effects are a ‘multiscalar counter offensive’ to neoliberal austerity urbanism (p. 264). The goal is to reconstruct public ownership as a grassroots project by making the commons the foundation of a renewed public sector (p. 267).

Thompson leaves it to others to examine whether the aspirations of these projects—the capacity to forge social solidarity against the alienation of atomization—are realized in the lived experience of residence, but he makes a persuasive case that collective alternatives are an important way to resist the dispossession wrought by capitalism.

Margaret Kohn, University of Toronto

Matthew Thompson 2020: Reconstructing Public Housing: Liverpool’s Hidden History of Collective Alternatives. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. Cover used with permission of Liverpool University Press.

Views expressed in this section are independent and do not represent the opinion of the editors.