“Gay Dance Clubs on the Wane in the Age of Grindr,” proclaimed the journalist Michael Musto in the New York Times in 2016. Musto, who has reported on gay life in New York for decades, had noticed a decline in weekly dance parties. In speaking to club promoters and performers, Musto kept hearing the same thing: people would rather meet others via the comfort of their mobile phones than in a gay space. (“Clubs have been usurped by the right swipe”; “Social media changed the landscape of going out”; “Why pay an expensive cover charge and deal with rude bouncers when you can just swipe on your iPhone?” and so forth.) Similarly, a New Orleans bartender told gay reporter Chris Staudinger: “You could ask any bartender in New Orleans whether the apps have affected business in gay bars, and they would all say yes.”

Scholarly research has also pointed to Grindr (and related platforms) as troublesome technologies that might obviate the need for urban gay spaces. Grindr (founded 2009) is a smartphone-only platform that allows mostly gay men (and also queer and trans people) to connect to others in their immediate vicinity via private messages. Related geo-social apps include gay platforms like Scruff, Hornet, Growler or Chappy, or the app versions of websites like Gaydar or PlanetRomeo, and mainstream equivalents like Tinder and Happn.

These geo-locative platforms challenge the idea that a “gay space” needs to be a physical space distinct from a straight space, since the “grids of the Grindr interface can be overlaid atop any space” (Roth 2016: 441). Consequently, authors such as Alan Collins and Stephen Drinkwater (2017: 767) argue that these platforms “displace (when deployed) the regular need for specific physical gay meeting venues… reducing the motivation and frequency of long-distance leisure commuting” to urban gay spaces. These various claims led geographers Ryan Centner and Martin Zebracki to organize two panels on urban gay spaces at the 2017 Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) annual conference. Importantly, the panels underscored the role of gentrification in shifting the gay urban landscape. Greggor Mattson (2017) noted that gay bar decline can be uneven: in the U.S., bars in smaller cities and/or frequented by women and people of color are hardest hit. Wouter Van Gent and Gerald Brugman (2017) argued that gay urban spaces might be less important to white, middle-class men (in Amsterdam and New York), but these spaces are central to the identity formation of men with immigration background.

I’ve been doing research on Grindr in the greater Copenhagen area since 2015, with a special focus on how immigrants and those who are “new in town” use the platform (see e.g. Shield 2017, 2018). Grindr is usually referred to as a “hook-up” or sex app, but my research shows something different. Especially newcomers use the app for a variety of platonic and logistical reasons: to find housing, make friends, find local guides to show them the city, or to learn about events. For some of these reasons, and as I argue here, Grindr has not necessarily affected Grindr users’ willingness to go to gay spaces; to the contrary, Grindr may actually bring many new gay men and queer people to LGBTQ urban spaces.

My research centers on interviews with sixteen recent immigrants to Copenhagen and Malmö (from China, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Nigeria, Turkey, among other places) and on an archive of 600 profiles with race- and migration-related texts collected from the greater Copenhagen area since 2015. I’ve asked questions about migrant-to-local networks, migrant-to-migrant networks, racial identification, and racism on Grindr. But in this Spotlight essay I draw on my research to critically assess the idea of Grindr as a disruptive urban technology that may render urban gay spaces obsolete, offering three arguments to support the claim that newcomers who use Grindr might actually bring new life to queer urban spaces, such as gay bars.

1. Newcomers don’t use Grindr in the same way they use (physical) queer spaces

There is an assumption that people use Grindr and gay bars for the same thing: to flirt and hook up. But both spaces host a variety of possibilities. People use Grindr not just to find sex, but also to make friends or merely participate in “social voyeurism” (a term media scholar danah boyd (2008: 10) used when describing teenagers’ use of social media). Newcomers in particular use Grindr for these purposes: “South African, New to Copenhagen, Looking to make some friends.” Others use it for logistical reasons, such as the Slovakian student whose Grindr headline last August read “Looking4room.”

Those who socialize via Grindr inevitably have to choose a physical space to meet these friends or dates. Gay bars often become that gathering space, especially for newcomers who might live peripherally, and/or with family. Similarly, tourists who use Grindr to find local tour guides might meet their prospective matches at a gay café: “Visiting. Drink a coffee or beer with me or show me the place!”

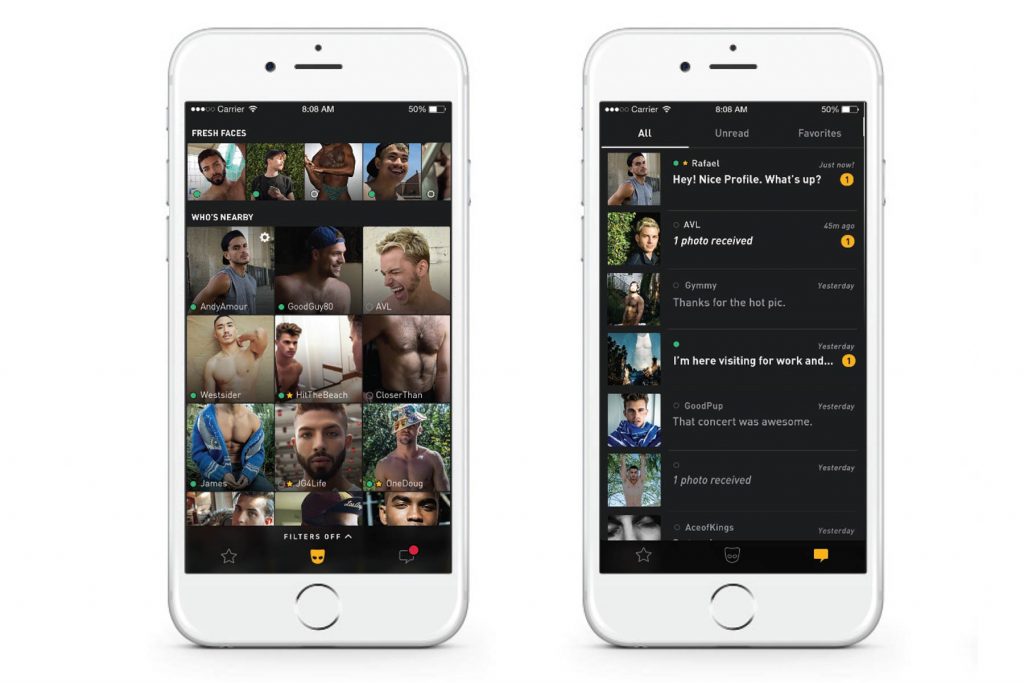

Screenshots of the Grindr App. Source: Grindr Press kit.

Newcomers also use Grindr to inquire about gay events. A local might inform the curious tourist about a monthly party in a peripheral venue that is only sometimes queer, or a queer performance opening that weekend. Thus Grindr can facilitate the newcomer’s access to lesser-known queer spaces.

2. Newcomers use Grindr in queer spaces.

Gay bars and other queer spaces can be intimidating for solo people. Some interviewees expressed that it was easier to initiate conversation with Scandinavians via Grindr than by approaching them at a bar. But these two venues are not distinct: many people, especially newcomers, use Grindr while located in gay spaces.

One interviewee, originally from Iran, learned about Grindr from another immigrant while patronizing one of Copenhagen’s late-night bars: “In Never Mind, I saw a Filipino guy, and he told me [about Grindr]. I saw people were doing something on their mobile, so I asked him: what are they doing? And, what are the websites that can find friends? And he told me, that’s Grindr.” The Filipino man gave him a tour of the platform, and in doing so, they overlaid the physical space of the gay bar with the online space of Grindr. Also, a tourist looking to browse Grindr might relocate to a gay venue to do so. Otherwise on the street or at a “regular” café, the tourist risks broadcasting his flirtatious communiqués to an unintended audience. At a gay venue, the tourist might feel more comfortable using the app openly, and could end up inviting a nearby user to join him.

3. Newcomers often have better luck finding sex offline.

Not everyone’s best assets shine through via Grindr. Public profiles center on one profile photo, about fifty words of text, and some drop-down menus. Visual cues dominate, and many find it difficult to convey aspects of their personality—humor, wit, charm—or stature, voice timbre, and so forth.

Many immigrants and people of color face racism on Grindr: “I apologize but asians is a polite ‘no thank you,’” declares one Copenhagener brusquely on his profile. One Arab interviewee confronted more racism and xenophobia on Grindr than offline: “On Grindr usually people just say whatever they want to. Because they don’t know you, and there is a distance, and it’s only chat.” Offline, people avoid confrontation. In a gay bar setting, this might mean that fewer would flatly deny conversation based on one’s race.

Relatedly, Grindr can be difficult for “discreet” users who are unwilling to share clear face photos for privacy reasons. A Middle Eastern interviewee preferred not to share photos via Grindr due to concerns about members of his diasporic community learning that he was gay. Ultimately his countless Grindr conversations ended with nothing. But as he explored Copenhagen’s gay spaces – including the gay sauna – he had better luck finding connections offline.

***

One should not overemphasize the emancipatory aspects of Grindr (and related platforms), especially with regard to migrants’ adaptation processes; and this caveat extends beyond arguments about racist and xenophobic chats. Geo-locative technologies also tend to reinforce a user’s physical geography; in an urban context, this means that those living in peripheral urban communities or suburbs – such as “immigrant neighborhoods” or “ghettos” – become invisible to those using the app in high-congestion areas. Thus geo-locative apps can reproduce urban divisions in a virtual space – divisions that are not only physical, but also social, ethnic and/or racial.

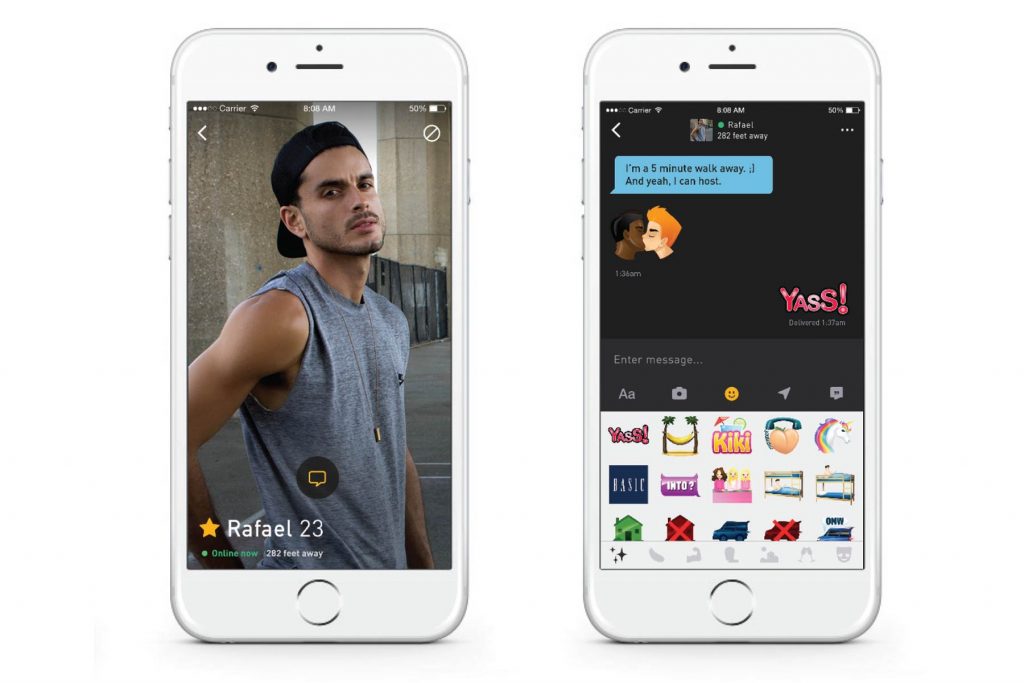

Screenshots of the Grindr App. Source: Grindr Press Kit.

Yet there are still areas for future research regarding Grindr’s potential to nurture urban queer spaces. Media scholar Sharif Mowlabocus was one of the first researchers to publish about Grindr. Comparing the geo-locative app to website cultures, Mowlabocus noted Grindr’s radical potential to “reintegrate gay men back into public space” as “digital cruising can and does occur ‘on the street’” (2010: 195). Future research should take this proposition seriously, and examine how Grindr (and related platforms) interact with urban spaces in more nuanced ways than those asserted by the bartenders and party promoters at the start of this piece. These technologies have some potential to revitalize gay urban spaces, including not only gay cafés and bars (as this piece suggests), but also the historically important non-commercial venues of public sex (e.g. cruising areas in parks and public toilets), and other urban queer spaces like drop-in centers, queer art exhibits, and performance venues.

Andrew DJ Shield is the author of Immigrants in the Sexual Revolution: Perceptions and Participation in Northwest Europe (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017). He holds a PhD in history from the City University of New York (CUNY) Graduate Center, and awaits a second PhD in communication from Roskilde University (Denmark) for the project “Immigrants on Grindr,” funded by the Danish Council for Independent Research. He has a B.A. from Brown University.

All essays on Disruptive Urban Technologies

Gay Immigrants and Grindr: Revitalizing Queer Urban Spaces?

Andrew DJ Shield

Disruptive 3D Geospatial Technologies for Planning and Managing Cities

Rob Kitchin

What Can ‘Disruptive Urban Technologies’ Tell Us about Power, Visibility and the Right to the City?

Linnet Taylor

Related IJURR articles on Disruptive Technologies

Physical Place and Cyberplace: The Rise of Personalized Networking

Barry Wellman

The Internet and Civil Society: Environmental and Labour Organizations in Hong Kong

Yin‐Wah Chu, James T.H. Tang

‘Call if You Have Trouble’: Mobile Phones and Safety among College Students

Jack Nasar, Peter Hecht, Richard Wener

‘So Long as I Take my Mobile’: Mobile Phones, Urban Life and Geographies of Young People’s Safety

Rachel Pain, Sue Grundy, Sally Gill, Elizabeth Towner, Geoff Sparks, Kate Hughes

Networking Cities: Telematics in Urban Policy — A Critical Review*

Stephen Graham

‘Tuning Out’ or ‘Tuning in’? Mobile Music Listening and Intensified Encounters with the City

Allan Watson and Dominiqua Drakeford-Allen

Urban Operating Systems: Diagramming the City

Simon Marvin and Andrés Luque-Ayala

© 2018 THE AUTHOR. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF URBAN AND REGIONAL RESEARCH, PUBLISHED BY JOHN WILEY & SONS LTD UNDER LICENSE BY URBAN RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS LIMITED

This is an open access essay under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License, which permits use and distribution in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, the use is non-commercial and no modifications or adaptations are made.