Ethel Harris lives in a neighborhood near Detroit’s airport where weeds are overgrown on abandoned lots and the majority of homes face foreclosure.[1] After her previous home was damaged in a fire, Ethel negotiated an informal arrangement with the property owner’s grandson who was only too willing to rid himself of the rundown house, its taxes, and its utility bills. Unfortunately Ethel was promptly slapped with a $2,500 bill from the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department amounting to arrears from the last two years—a bill that she, as a low-income resident with an autistic dependent, could scarcely afford to pay. While past-due bills are typically wiped for the new owner of a foreclosed property, Ethel’s side arrangement with the owner’s grandson meant that she had a difficult time furnishing the necessary paperwork to have the water debt forgiven. Faced with the threat of a cut-off in a city where one in ten homes had their taps at least temporarily shut in 2017, she entered into a payment plan that waived her right to dispute the bill. “It’s not fair. But I gotta do what I gotta do,” Ethel says in an interview on Michigan’s National Public Radio station. “I have to pay in order to stay here. I want to stay here, and have to have water”.

Ethel’s story is far from unique. Between 2014-2017, tens of thousands of Detroiters lost their water connections because of outstanding bills, sparking international human rights criticism. Utilities in America want to use cut-offs as a warning to stem what they call a “culture of non-payment”, a discourse startlingly similar to what was used to discipline poor blacks in post-apartheid South Africa (von Schnitzler, 2008). Such a discourse, crafted in the context of municipal bankruptcy and neoliberal austerity, elides the fact that America’s poorest face unique challenges in terms of lacking formal property tenure, paperwork, credit, and a steady income. These are conditions that at first glance seem out of place in America. Indeed, when the media covers a water-related crisis here, such as the ones witnessed in post-industrial cities like Detroit and Flint; California’s Central Valley, Texas’ borderlands, or America’s southern states, facile comparisons to the ‘Third World’ are offered, as if to single out the region as anomalous in an advanced country that otherwise delivers on its promise of safe, reliable, and affordable water and sanitation. Yet such Third World comparisons belie a more pervasive geography of racialized water poverty in a country where low-income people of color are disproportionately hit with unavailable, unsafe, and/or unaffordable water and sanitation. There has been little systematic accounting of this situation. Below I outline the broad contours of a geography of water, race, and poverty in America, one that should be understood as neither random nor accidental.

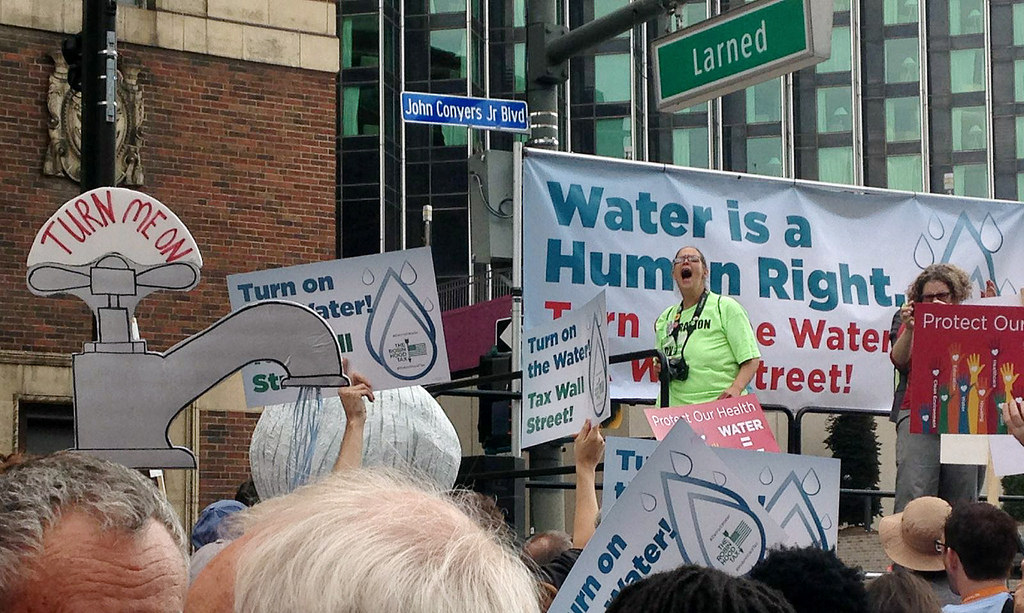

Detroit Water Shutoff Rally, 2014. Photo: uusc4all/Flickr. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

1. Histories of racial segregation undergird water abjection in America

As I have written previously (Ranganathan, 2016), Flint’s lead poisoning afflicting the city’s youngest and predominantly African American residents should be understood as the slow burn of racial liberalism. By that I meant that despite the presence of policies and attitudes favoring individual liberties and freedoms in America—paramount of which is the right to own private property—liberal planning in practice has encoded racial hierarchies in the valuation, management, and taking of property via decades of redlining, racialized covenants, discriminatory zoning, exclusionary suburban development, and myriad other practices of racial segregation. Property serves as an “essential race-making institution” (Bonds, 2018: 2). Combined with post-industrial economic decline, these practices have gutted Flint’s tax base. Under the logics of “colorblind” austerity urbanism, however, Flint’s predicament is diagnosed not as the accretion of these historical factors, but rather the result of its financial recklessness—the lives of its residents thus devalued and subject to cheaper, poisoned water, or what Laura Pulido (2016: 1) refers to as the “everyday functioning of racial capitalism”. That racial and spatial segregation is institutionalized in planning tends to be erased in simplistic narratives comparing water deprivation in America to the Global South.

Lead poisoning and water cut-offs are not the only indicators of household water insecurity, understood as insufficient and unreliable water for domestic consumption and human well-being. Water insecurity is shaped, in turn, by wider social, political, and material relations (Jepson et al. 2017). A new study by Shiloh Deitz and Katie Meehan (Forthcoming) draws on household census data across the US to argue that incomplete plumbing—that is, the absence of running water, a flush toilet, and/or a working shower or bath—is a poorly understood phenomenon that affects over half a million households in the country. Across the US, what these authors refer to as “plumbing poverty” manifests four times as much in American Indian and Alaska Native households, 1.2 times as much in African American households, and 1.2 times as much in Latinx-Hispanic households as compared to other households in similar conditions. In other words, race matters for plumbing, and is more significant than measures of class, housing, or rurality taken alone.

Place also matters. The US contains racialized “hot-spots” of plumbing poverty (i.e. higher than expected rates) in areas that have been deeply disenfranchised and subject to settler-colonial and white supremacist logics, such as the “Black Belt” in the US South, Native American reservations, and colonias[2] along the US-Mexico border.

2. Water insecurity is intersectional and varies geographically

Race consistently predicts lack of or contaminated water, but intersects with other factors that shift across the country. That is, water insecurity in America, as elsewhere in the world, is intersectional and geographically-specific—shaped by interacting axes of social, economic, cultural, and place-based difference. At the US-Mexico border and California’s San Joaquin Valley, for instance, it is race interacting with citizenship (e.g. undocumented immigrant status), linguistic discrimination, and/or the unincorporated status [3] of peripheral areas that most determines household water insecurity (Balazs and Ray, 2014; Jepson and Vandewalle, 2016; Ranganathan and Balazs, 2015). Meanwhile in Lowndes County, Alabama—home to some of America’s greatest civil rights struggles—it is race and poverty, themselves etched by histories of planation slavery and racial capitalism, interacting with the prevalence of mobile homes and the absence of sanitation, that underlies insecurity. Specifically, this insecurity takes the shape of hookworm disease caused by a parasite that enters the body through exposed skin and impairs digestion and cognitive functioning. In one study, hookworm was found to affect one in three Lowndes County residents participating in the study (McKenna et. al, 2017). While the hookworm rate in the larger population is likely lower than this, the incidence of the disease can nevertheless be traced to the area’s woefully inadequate septic systems. Raw sewage, awash on loamy clay soils that were once tilled by slaves for cotton plantations, provides the ideal breeding ground for hookworm. As Danielle Purifoy (2016) narrates, the lack of public spending on safe sanitation in Lowndes County has been devastating for Black property and wealth generation across the South, perpetuating a historical cycle of racialized property dispossession and health disparities that is all too familiar.

Finally, the question of gender and water has not been investigated in America to the extent that it has in the Global South. Yet property-related challenges, such as eviction and homelessness, are undoubtedly gendered and raced. Poor Black women, especially single mothers, are the face of America’s eviction crisis. If in the Global South, slum dwellers and other precariously tenured groups pay a significant amount of their monthly incomes to procure water—often from unregulated informal providers—in America, that relationship cuts both ways: not only do the poor often pay more than the federally-recommended 4.5% of monthly income on water, but expensive water bills and plumbing-related issues can, in turn, force foreclosure, eviction, and homelessness disproportionately on low-income mothers of color.

3. Public spending on infrastructure and affordability: An Anti-Racist New Deal?

A third and final reality: much of America’s modern water and wastewater infrastructure, influenced by breakthroughs in germ theory and hygiene in the late 19th century, dates to the New Deal and the end of World War II (1930s-1940s). This means that water infrastructure is aging and is likely to be more susceptible to break-down with climate change. Some estimate that it would cost over $1 trillion dollars in the next 25 years to replace systems built mid-20th century, which could triple the cost of household water bills and, given stagnant incomes, result in a third of Americans unable to pay their bills by 2020 (Mack and Wrase, 2017). Some cities, such as Atlanta, have already resorted to privatization, drastically increasing water rates. Even without privatization, utilities and cities feel compelled to raise rates to cover the costs of repair. Such rate increases would be disastrous for low-income minority families.

Now and in the future, America needs a New Deal for water infrastructure that does not repeat the structural racism of the 20th century—an anti-racist New Deal, perhaps, that explicitly tackles the challenges of water, race, and poverty that persist across the country’s unequal geographies. Part of this plan would involve directing public investment to financially gutted, abandoned, and deeply segregated cities and small towns. Part would involve restructuring tariffs progressively so that lower-income families face lower tariffs, and so that the historical cycle between racialized property and unequal access to vital, life-sustaining infrastructures is disrupted. In this, there may be lessons to be learned from cities in the Global South.

Malini Ranganathan (American University, School of International Service)

All essays on Parched Cities, Parched Citizens

Introduction

Liza Weinstein

Water Crisis

Nikhil Anand

Beyond ‘Third World’ Comparisons: America’s Geography of Water, Race, and Poverty

Malini Ranganathan

Crisis Temporalities: Intersections Between Infrastructure and Inequality in the Cape Town Water Crisis

Suraya Scheba & Nate Millington

Water Scarcity Beyond Crisis: Spotlight on Accra

Megan Peloso, Cynthia Morinville & Leila M. Harris

Water Crisis and Eco-Apartheid in São Paulo: Beyond Naive Optimism About Climate-Linked Disasters

Daniel Aldana Cohen

Related IJURR articles on Parched Cities, Parched Citizens

Conduct of conduits: engineering, desire and government through the enclosure and exposure of urban water.

Usher, Mark

Urban Warfare Ecology: A Study of Water Supply in Basrah.

Zeitoun, Mark, et al.

Worlding water supply: thinking beyond the network in Jakarta.

Furlong, Kathryn, and Michelle Kooy

The political ecology of virtual water in Southern Spain.

Beltrán, Maria J., and Esther Velázquez

Debate on Karen Bakker’s Privatizing Water.

Punjabi, Bharat

Paying for pipes, claiming citizenship: Political agency and water reforms at the urban periphery.

Ranganathan, Malini

Experiments and counter‐experiments in the urban laboratory of water‐supply partnerships in India.

Gopakumar, Govind

The Changing Nature of Border, Scale and the Production of Hong Kong’s Water Supply System since 1959.

Lee, Nelson K

Atlantic gardens in Mediterranean climates: Understanding the production of suburban natures in Barcelona.

Parés, Marc, Hug March, and David Saurí

Maintaining climate change experiments: urban political ecology and the everyday reconfiguration of urban infrastructure.

Broto, Vanesa Castán, and Harriet Bulkeley

Gender water networks: femininity and masculinity in water politics in Bolivia.

Laurie, Nina

© 2018 THE AUTHOR. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF URBAN AND REGIONAL RESEARCH, PUBLISHED BY JOHN WILEY & SONS LTD UNDER LICENSE BY URBAN RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS LIMITED

This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License, which permits use and distribution in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, the use is non-commercial and no modifications or adaptations are made.