‘From the rural areas to the city, we are anonymous Black women: the landless, the farmhands, the servants, the domestic workers, the street sweepers, that, in some form or another, are present in the struggle by organizing themselves in the unions, in the class associations, in the peripheral neighborhood and favela movements.’

–Lélia Gonzalez, “Prefácio à obra poética de Alzira Rufino,” 1988

‘The bourgeoisie is fearful of the Negro woman, and for good reason. The capitalists know, far better than many progressives seem to know, that once Negro women undertake action, the militancy of the whole Negro people, and thus of the entire anti-imperialist coalition, is greatly advanced.’

–Claudia Jones, “An End to the Neglect of the Negro Woman,” 1949

Amid all the criticism of his leadership that right-wing Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro has received, there are many who believe that the Left in Brazil has a strong chance of reclaiming power in the 2022 presidential elections. Bolsonaro’s ongoing mismanagement of the coronavirus pandemic, his support for the corporate degradation of the country’s natural resources, and his role in the deepening of the economic crisis as well as the promotion of militarized racial, gender, and homophobic violence have consolidated the opposition leadership prepared for radical transformation. In all recent presidential polls, former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (popularly known as Lula) of the Workers’ Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores, PT), freed from prison with all charges against him dropped, leads over Bolsonaro (Pesquisa Datafolha para presidente: Lula tem 47%; Bolsonaro, 28; Ciro, 8%, 23 June 2022). Lula is expected to officially announce his candidacy in July, and he has already been travelling around the world, meeting with heads of state. Throughout Brazil, Lula is making an effort to talk with leaders of the Black, feminist, favela, and land/houseless movements, reassuring them that he can represent their political interests in the years ahead.

As researchers who write and lecture about women and politics in the Americas, (see our recent introduction to our Portuguese translation of Claudia Jones’s classic 1949 essay, “An End to the Neglect of the Negro Woman”), in this essay, we take on the challenging question of why no serious Black woman presidential candidate has emerged in advance of the 2022 Brazilian elections. Recent scholarship has shown how Black women in the country have been central in organizing rural and urban communities and mass movements (Prestes 2018; Pereira 2019). We focus on why they face numerous barriers to being viable candidates within parties, despite their proven political competency and persistent energy in social movements.

In spite of Lula’s political gesture, Black leaders, among them several women, point out the Left’s difficulty dealing with serious problems affecting the Black population in Brazil, such as State-sanctioned violence against Black people. In 2016, the federally funded Institute of Economic Research (IPEA) and the Brazilian Forum of Public Security (FBSP) created the Atlas da Violência, and Julio Jacobo Waiselfisz published the first of his annual reports, the Mapa da Violência. Both reports have shown that since 1980, Black people have disproportionately been the majority (77%) of the victims of homicidal violence. Additionally, 67% of the women victims are Black, most of them young people between the ages of 15 and 29 (Atlas da Violência 2021). Black scholars and activists have argued that a genocide is taking place against Black people, and the militarization of the police war against the poorest urban communities in the capital cities has intensified, including while Lula and Dilma Rousseff were in office (Nascimento 2016; Flauzina 2014).

They also argue for the urgent need to open spaces for a more significant presence of Black people in positions of power in the PT and its governments. Lula and Dilma’s presidential cabinets had few Blacks (including Luiza Bairros, Gilberto Gil, Matilde Ribeiro, Edson Santos, Nilma Lino Gomes, Benedita da Silva, and Orlando Silva). Recently, in a meeting with Lula, Bahian activist-intellectual Vilma Reis addressed this issue, pointing out that if Lula is elected to a third term, Black people must be appointed to positions in all areas of the government: “We are here to say that we are ready to act as secretaries in the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Education, or in the Brazilian diplomacy” (“Vilma Reis: Liderança do Movimento Negro…,” 2021).

Debate with Vilma Reis in Casa Mídia Ninja Bahia in Salvador, 2020. Photo: midianinja, CC BY-NC 2.0.

A longtime activist of Black and Black women’s movements in Brazil as well as a sociologist who researches police killings and openly criticizes state violence, Reis recently tried unsuccessfully to run for mayor of Salvador, Bahia, the northeastern Brazilian city with the largest concentration of Blacks in the African diaspora and the second largest Black population of any city in the world, after Lagos, Nigeria. Instead of Reis (who pushed the Left to take a stance on the genocidal killings), the PT chose an unknown Black woman police officer that they believed could “tow the party line,” but who Black party members and grassroots activists vehemently opposed because of her relationship to the police state.

More than 30 years ago, another Black feminist activist-intellectual, Lélia Gonzalez, termed the difficulty the PT had dealing with the Brazilian Black population’s problems “racismo por omissão” (racism by default), which she explained was “one of the aspects of the whitening ideology that, based on colonization, wants to make us believe that we are a racially white country and culturally Western, Eurocentric” (Gonzalez 2020). In essence, the Left in Brazil projects itself as White, and this includes the PT and other political parties identified with this side of the political spectrum. This is despite the political fact that the Left relies on most of the Black population voting for it, especially the “anonymous Black women” (Gonzalez 1988) workers moving between rural areas and cities. In addition to Lula, other leftists are emerging on the political scene as potential presidential candidates, most of them representing different political perspectives. However, in a country with a majority Black population estimated at 55%, what they all have in common at this point is that they are all White men.

Benedita da Silva (affectionately known as Bené) was a neighborhood activist in Rio de Janeiro who, in 1982, became the first Black woman to be elected to the Brazilian Congress; she was later appointed as Lula’s Minister of Social Development. In her memoir (Silva 1997), she writes that there is a basic assumption that politics is solely for men, and that only White men have what it takes to be politicians. There is a general underrepresentation of women in office at the city, state, and national levels in Brazil. Nationally, as a result of the 2018 elections, women currently occupy 15% of seats in the Chamber of Deputies, filling 77 of 513 seats (Agência Câmara Notícias 2018). Even though women comprise more than 50% of the country’s population, the leadership contrasts greatly with other countries in Latin America, such as Bolivia and Costa Rica, where women occupy more than 30% of seats in the national legislatures. The presence of Black women has increased in the Brazilian Chamber of Deputies, with constant growth during the last terms, from three women elected in 2006 to 13 in 2018. The number of candidates has also increased. More than 1,000 Black women ran for office in the 2018 elections, a 151% increase since the 2014 election cycle (Isabella Macedo and Lucio Big 2018). Thus while their participation in politics as both activists and candidates is growing, they remain a small minority in positions of power.

To further understand the ideological and structural problems for activist-intellectuals such as Reis in the country’s major cities who aspire to lead locally and nationally, a more historical context of Black women’s political activism in Brazil is needed. The main challenge is that the political parties, including leftists, do not perceive Black women as viable candidates because there is a basic assumption that they are not interested in politics (Meneguello 2012). Based on the political trajectory of Black women activists and their leadership in organizations, as well as their unique intersectional approach to politics in Brazil, we know that Black women are not only viable as presidential candidates to represent the Left, they are the main ones moving the agenda even more to the Left, expanding the collective understanding of class inequality to include race, gender, sexuality, and region. As Reis has stated, “We are the ones who push the Left to the Left in Brazil because the agenda of the Black movement was always an emancipatory and progressive agenda, positioned within the most advanced agendas in Brazil and the world” (São mulheres negras que empurram a esquerda para a esquerda, 20 July 2020). In this vein, she also says, “We have built the careers of all the White progressives in this country. Our understanding now is that it is no longer possible to ask us to wait. All of the building of social movements that comes from the streets into the parties would not be possible without us” (Decidimos interromper a hegemonia branca na política, 14 December 2019).

Black Brazilian women have been mobilizing independently as a collective political force over the last few decades. Activist-scholar Sueli Carneiro, director of Geledés, one of the country’s most prominent Black women’s organizations located in São Paulo, often says, “Between the Left and the Right, I am still a Black woman.” More than a call to depoliticize Black people, this saying is an invitation to bring to light a view on racial issues and blackness not as conditional issues in Brazilian party politics but as constitutive elements. Carneiro recognizes that a country that was built entirely on the exploited labor of Black and Indigenous peoples cannot repair the legacies of class inequality without addressing the peculiarities of racial, gender, and sexual marginality. Radical social and economic transformation in Brazil requires addressing the systemic dimensions of racial and gender exclusion. Most urgently, the State-sponsored killings of Black youth in cities, mass displacements of Blacks in cities for mega-sports events and urban redevelopment, and inadequate public health, transportation, and education need to be central public policy issues, along with transgender murders, which increased by 41% in 2020––68% of those murders were of Black women (Lu Sudré 2021).

Despite such persistent inequalities and violence, many still see the political parties on the Left as the only space for Black women to build political careers based on emancipatory proposals for social justice and repair in Brazil. However, these same parties continue to struggle to recognize Black women’s political and organizational capacity to occupy positions within the parties and be considered potential candidates for the executive branch of government (such as mayors, governors, and the presidency). Trinidadian activist-intellectual Claudia Jones made this key point more than 70 years ago when she criticized the Communist Party USA’s neglect of Black women among its ranks to serve in leadership positions and use the knowledge they gained as super-exploited workers as well as community organizers (Jones 1949).

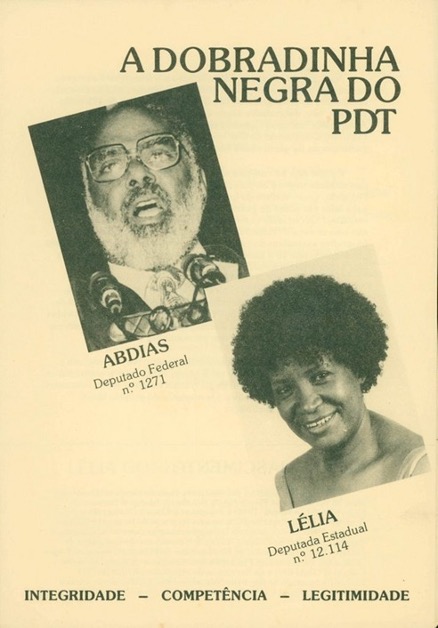

Renowned Black Brazilian writer Carolina Maria de Jesus wrote in her book Child of the Dark, first published in 1960, “Brazil needs to be led by a person who has known hunger. Hunger is also a teacher. [A person] who has experienced hunger learns to think of the future and of the children.” Black women throughout Brazil are the main political protagonists in social movements organized to combat hunger and fight for housing, land rights, access to public health and education, and against police violence. As a Black movement founder, feminist intellectual, and human rights activist, Lélia Gonzalez had the profile and disposition to be a presidential candidate in the 1980s and 90s. When she ran for the federal Legislative Assembly in 1982, she was instead chosen as the alternate for the PT, forcing her to move to the Democratic Labour Party in the 1986 elections, for which she was also chosen as a substitute.

Campaign pamphlet for Lélia Gonzalez and Abdias Nascimento, 1982; Courtesy of the Anani Dzidzienyo Collections. Photo: Keisha-Khan Perry

In recent years, except for Benedita da Silva and Marina Silva, who became federal senators as PT candidates, few Black women have been elected to national positions or at the municipal and state levels. Most of the elected Black women have run with other political parties, such as the Socialism and Liberty Party (PSOL), the party represented by openly lesbian Marielle Franco (city councilwoman) in Rio de Janeiro, as well as transwomen Erika Hilton (city councilwoman) and Erica Malunguinho (state representative) in São Paulo. This demonstrates the continued faith in the Left to advance a feminist and antiracism agenda but also reflects the limitations of political advancement within the current PT. As many of these politicians have stated, “The way out is through the Left,” but we must ask, what kind of Left do we want? The answer that Reis has offered is, “We want our own emancipatory and democratic political projects,” meaning that Black women want to lead autonomously without being forced to carry a party’s political projects that do not reflect the racial and gender realities of the cities and country in which they live.

Marielle Franco. Photo: Oto_Jr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

The movement of Black women accessing politics and the increase in representation reflect distinct factors. One of them is the result of the spark of mobilization in Brazilian cities generated after the assassination of Marielle Franco. The founding of the Marielle Franco Institute in her memory with the explicit aim of supporting Black women’s political ambitions (beyond the political parties of the Left) has already been impactful. The institute organized the Marielle Franco Agenda in advance of the 2020 elections, outlining a series of racial, class, gender, and LGBTQ+ issues that Marielle defended as part of the legacy of Black Left feminist political demands in Rio de Janeiro and Brazil. Another organization, Fundo Baobá, organized the Racial Program for the Acceleration of the Development of Black Women Leaders (which also honored Marielle Franco) as a political school that brought together activist-intellectuals like Reis, housing movement activists, and others who wanted to pursue careers in politics. Thus, if we pay attention to the history of the Black women’s movement in Brazil in recent decades, we can better understand how their actions paved the way for this political moment. A legacy of Black women’s political activism has been passed down through the generations; Marielle Franco was an heir of this legacy and is now an inspiration. As in the case of Benedita da Silva, who emerged from Rio de Janeiro’s favela movements of the 1980s, Franco’s transition from neighborhood movements to electoral politics reflects a common trajectory in the formation of Black women politicians. Ironically, only after her assassination was Franco discussed as a serious prospect for president of Brazil. Former public school teacher Olivia Santana served several years as a councilwoman in the city of Salvador and was elected to the Bahian State Assembly in 2018, one of only a few to make this political leap beyond city government. In addition to making history as a Black trans candidate, Erika Hilton was the woman who received the most votes in São Paulo, the largest city in Brazil; hence, she received the most votes of any woman in the country. However, there are few possibilities for political advancement for Santana, Hilton, and other Black women on the Left beyond city government.

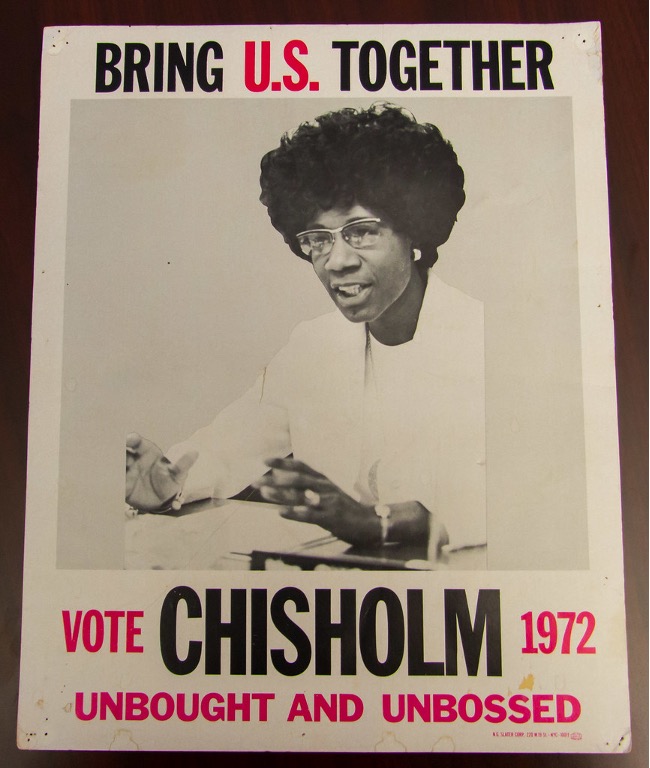

In the Americas, it is not entirely far-fetched to imagine a Black woman presidential candidate and even a president in the country with the largest population of African descendants outside of Africa. It is important to remember that amid Jim Crow (state and local laws enforcing segregation in the United States), Shirley Chisholm started her career as a New York City schoolteacher and education consultant in the 1950s, then became a city councilwoman and a New York State representative, and finally ran for president of the United States in 1972.

Shirley Chisholm Campaign Poster: Seattle City Council, CC0 1.0

Just as in that presidential race, when feminists and the Congressional Black Caucus rallied behind the candidacy of Democrat George McGovern instead of Chisholm (Chisholm 1973, 2010; Lynch 2005), there are many in Brazil who would argue that we need to hedge our bets by backing a candidate (regardless of race, gender, or sexuality) who can guarantee a win against Jair Bolsonaro or any other right-wing candidate who may emerge. Without necessary changes in how political parties perceive women as potential candidates, we will not see a growth in the number of female presidents (Dilma Rousseff was the first and only woman president and was unable to complete her second term) nor the first Black woman president, nor a radical shift in the representation of leadership in Brazil. On the African continent, there have been nine women presidents, including the current president of Ethiopia, Sahle-Work Zewde. In the Caribbean, Mia Mottley is currently the Barbadian prime minister and Epsy Campbell-Barr is the vice-president of Costa Rica. In Colombia, the country in Latin America with the second-largest Black population, environmental activist Francia Márquez ran for president within the Pacto Histórico coalition and later won as Vice President to the presidential frontrunner Gustavo Petro. As political scientist Maziki Thame argues in her essay, “Women Out of Place,” on former prime minister Portia Simpson-Miller, the election of a Black woman who emerged from the grassroots of the People’s National Party subverted the hegemony of a non-Black/Creole elite in post-independence Jamaica (in Jordan-Zachery and Alexander Floyd 2018). The November 2021 election of Xiomara Castro Sarmiento as Honduras’s first female president provides a strong example of standing behind more women at the highest level of electoral politics who can win on a platform of radical oppositional change.

Brazilian politician Gleisi Hoffman, unwavering in her politics and one of the most vocal defenders of the ousted Rousseff, emerged as a potential presidential candidate for the PT while Lula was still incarcerated. However, if Brazilians do not stand behind or promote Black women like Talíria Petrone of Rio de Janeiro and Áurea Carolina of Minas Gerais, we may never see a woman in office who shares a sense of common humanity across differences and key values around dismantling class inequalities structured by race, gender, and sexuality. Black Leftist women politicians need to continue to run for office at the city, state, and national levels, and we need to support them until Brazil gets its first Left-leaning Black female president. We can observe this kind of optimism and mass support for Márquez of Colombia, who had to join a coalition formed outside of the exclusionary politics of traditional parties, which is similar to the challenges that Brazilian Black women on the Left face within the parties in which they have long participated. In this context of Márquez’s inspiring political advancement, in Brazil, we recently observed strong criticism of an iconic photograph of Lula and a group of all white and majority male members of the PT and the Socialist Party of Brazil (PSB) who are forming a presidential coalition. This is a hemispheric problem across the Americas which begets the question of whether the party system as it currently stands in Brazil has become obsolete for a project of radical social change that attends to the needs of the majority Black population. Considering the limited range of the Leftist political agenda, we affirm that it may be time for Black people, including Black women, in Brazil to organize a new political party that prioritizes what historian Kim Butler (1998) has called the long abolitionist “struggle for full citizenship” in the country.

Keisha-Khan Y. Perry (Twitter) is the Presidential Penn Compact Associate Professor of Africana Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. Her research focuses on Black land ownership and loss, housing evictions, and the related gendered racial logics of Black dispossession in the Americas.

Edilza Sotero (Twitter) is a sociologist and professor of Education at the Federal University of Bahia. She writes about Black women’s intellectual histories and politics in Brazil and their diasporic linkages to the broader Americas.

All essays on Racial Capitalism

Introduction: Racial Capitalism

Nik Theodore

The Stuff of Life: Frontier Infrastructures of Reproduction

Omar Jabary Salamanca

Racial Violence is Woven into the Fabric of our Cities

Libby Porter

The Cost of Platinum: Legacies of Violence and Subordination of Black Miners in South Africa’s Mining Towns

Asanda Benya

Policing, Racial Capitalism and the Ideological Struggle Over Public Safety

M.M. Ramírez

Blackness and Metropolitan Adjacency

AbdouMaliq Simone

Black Women on the Left of the Left in Brazilian Politics

Keisha-Khan Y. Perry & Edilza Sotero

Related IJURR articles on Racial Capitalism

Hamburg’s Spaces of Danger: Race, Violence and Memory in a Contemporary Global City

Key Macfarlane & Katharyne Mitchell

The Nomad, The Squatter and the State: Roma Racialization and Spatial Politics in Italy

Gaja Maestri

The Limits of Homeownership: Racial Capitalism, Black Wealth, and the Appreciation Gap in Atlanta

Scott N. Markley, Taylor J. Hafley, Coleman A. Allums, Steven R. Holloway & Hee Cheol Chung

Reappearance of the Public: Placemaking, Minoritization and Resistance in Detroit

Alesia Montgomery

Geographies of Algorithmic Violence: Redlining the Smart City

Sara Safransky

Sowing Seeds of Displacement: Gentrification and Food Justice in Oakland, CA

Alison Hope Alkon & Josh Cadji

‘Wilding’ in the West Village: Queer Space, Racism and Jane Jacobs Hagiography

Johan Andersson

‘Troubled Assets’: The Financial Emergency and Racialized Risk

Philip Ashton

Racialization and Rescaling: Post‐Katrina Rebuilding and the Louisiana Road Home Program

Kevin Fox Gotham

Race and the Production of Extreme Land Abandonment in the American Rust Belt

Jason Hackworth

Talkin’ ’bout the Ghetto: Popular Culture and Urban Imaginaries of Immobility

Rivke Jaffe

The Structural Origins of Territorial Stigma: Water and Racial Politics in Metropolitan Detroit, 1950s–2010s

Dana Kornberg

Controlling Mobility and Regulation in Urban Space: Muslim Pilgrims to Mecca in Colonial Bombay, 1880–1914

Nick Lombardo

Neoliberalism, Race and the Redefining of Urban Redevelopment

Christopher Mele

Reconfiguring Belonging in the Suburban US South: Diversity, ‘Merit’ and the Persistence of White Privilege

Caroline R. Nagel

Race Matters: The Materiality of Domopolitics in the Peripheries of Rome

Ana Ivasiuc

Fear and Loathing (of others): Race, Class and Contestation of Space in Washington, DC

Brandi Thompson Summers & Katheryn Howell

Everyday Roma Stigmatization: Racialized Urban Encounters, Collective Histories and Fragmented Habitus

Remus Creţan, Petr Kupka, Ryan Powell & Václav Walach

Disaster Colonialism: A Commentary on Disasters beyond Singular Events to Structural Violence

Danielle Zoe Rivera

The Aesthetics of Gentrification: Modern Art, Settler Colonialism, and Anti-Colonialism in Washington, DC

Johanna Bockman

Beyond the Enclave of Urban Theory

Austin Zeiderman